Jens Pepper: Since I am in Warsaw, and step by step gaining access to the city’s photo scene and to Poland in general, I see your photos in publications and hear of you as one of the country’s major photographers of the last few decades, focusing on journalistic and documentary photography. Many of your images also became well known abroad, for you worked for international magazines like Newsweek, Time and Spiegel, and in 1987 you were winner of a World Press Photo Award for a portrait of the General Secretary of the Hungarian Socialist Workers‘ Party János Kádár. When preparing for the interview I saw a little film about your 2015 solo exhibition opening at the Ney Gallery with another important Polish photographer, Tadeusz Rolke giving a short introduction to the show. The gallery was packed with visitors, many of them of younger generations, and lots of more people seem to have waited outside to get access to the gallery space. This is what happens to stars or to very popular persons. How do you see your own role in Polish photography?

Chris Niedenthal: How on earth am I supposed to answer this question? For some reason my role in Polish photography has become that of a middle-aged representative of the somewhat old-school way of photographing reality. Of course, I was much younger when I took most of my photographs from the “bad old days”, meaning the time of communism in Poland. The point here is that these photographs have gained in documentary value precisely because of this time gap. In other words, I had to wait 30 or so years for my photographs to be regarded as good documentary photography. But perhaps the most important point – made by many people – is that I came to Poland as an outsider. Sure, my background was Polish, but I was born in London, England five years after the end of World War Two, and I lived in London for 22 years before going to Poland in 1973 – ostensibly for 2-3 months – but eventually staying there until today.

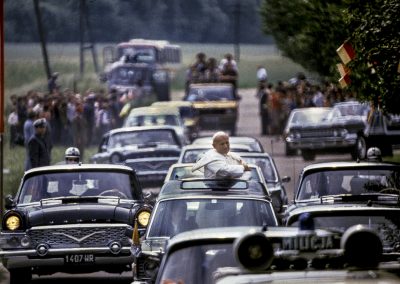

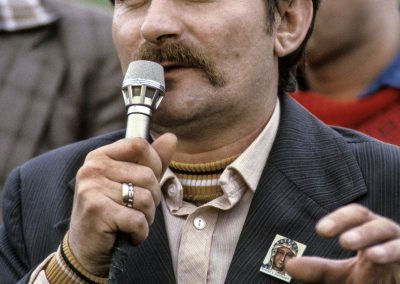

Of course I was lucky to have come to Poland shortly (well, several years first passed) before really interesting things were beginning to happen. In October 1978 a Polish Pope was chosen and bang! – I was the right guy in the right place at the right time. Then the historic strike in the Lenin Shipyard in Gdansk in August 1980 and bang! – there I was again, gaining experience in news photography of really important events.

By then I guess I was already part of the photographic world in Poland, but I had the added advantage of not having any problems with getting hold of western-quality colour films. For Newsweek, and later TIME, film was the smallest expense of our work, unlike Polish photographers who had great problems working on decent colour stock. That is why most of my work has been in colour, colour slide film to be precise as American magazines preferred to work with transparencies. So, for people used to seeing photographs from socialist days in black and white, my colour photographs appear to be different.

As to the crowd that came to my exhibition opening in January 2015, well, that was almost embarrassing, as a lot of people held it against me that they could not get in because of the crush, and the long line of people patiently waiting in the wind and rain. This was in large part due to the opening being announced on Facebook, a sure sign of the times when it comes to generating interest in virtually anything!

Jens Pepper: You mentioned your migration from London to Warsaw in the early 1970s. I guess, at the beginning you were just interested in the roots of your family. What made you stay? Carreer opportunities? A love affair?

Chris Niedenthal: Well yes, I must admit that at the beginning there was a girl involved in all this! She created the impulse; I did the rest! Other than that, I was just curious as to what life really looked like in Poland. Up until 1973 I had visited the country only on holiday, and I knew that the real Poland wouldn’t be quite so happy-go-lucky in more normal times of year. But as to family roots – I don’t recall being all that interested in such things when I was in my early twenties. After the war, my father had no family left in Poland, while my mother had two brothers in Warsaw, plus their families. And career opportunities? A nice point, but surely more applicable to people who want to be lawyers, doctors, or businessmen. Was I looking for career opportunities? Of course not. I was 22 and a half years old, wanting to be a photographer and trying to find my place in the world, and up until then I had never really felt all that interested in life in England. It was all too normal there, and having Polish blood in me I never really felt completely British. So in London I had the problem of being not quite British and not quite Polish. Poland just seemed far more interesting for me. Not the communist system, of course, nor the economic system. But I just found the young people far more friendly and amenable. In those days, I admit, being a foreigner in Poland was to a certain extent “quite something”: you had a western passport, you had western currency, you could leave the country whenever you wanted. All those things that the average Pole did not have and could not do. I started taking photographs straightaway, and slowly but surely I found myself being drawn in to life behind the Iron Curtain. In short, I just found the young people so much more interesting in Poland than back home in London. Social life, despite – or in fact in spite of – all the problems, was much more intense – and I loved it!

I must admit that I never told myself that yes, I am going to stay here in Poland forever. I just stayed for longer and longer, got married, had a child, and then historical events took over and there was no point in leaving.

Jens Pepper: You studied photography in London and wanted to become a photographer. After deciding to stay in Warsaw, was it obvious for you that you would earn your livelihood as a photo journalist?

Chris Niedenthal: During my three years of studying photography at the London College of Printing (today it is called, I think, the London College of Communication or something like that) I was firmly resolved to become a photojournalist. During the course we had to try fashion, advertising, even a bit of filming – but all the time I knew that it was only photojournalism that interested me. My tutors, I suspect, knew that too, and knew that whatever they asked me to do, I would produce a photojournalistic version of it.

My plan, on arriving in Warsaw for what I thought would be an extended three-four month stay, was to simply take photographs of daily life, and perhaps try to do some stories that could be sold in the western Press. I knew very well that that wouldn’t be easy, as Poland was of no interest to people in the West, especially to people in England or America. So I had very little hope at first to earn a lot of money back then. On the other hand, Poland had a flourishing black market, especially in western currencies, so I knew that I didn’t have to earn all that much to be able to live a relatively comfortable life in Warsaw. If I managed to earn 50 or 100 pounds sterling per month, I could live quite well on that. Of course that worked while I was still a young bachelor with no draining financial ties!

So yes, for me it was pretty obvious that I wanted to earn my living as a photojournalist. But of course it was not easy. My parents, at first, helped me a little bit, or in fact quite a bit, but my Father had always had other ideas for his son – he had wanted me to study economics at university, so that I could eventually get a “real” job. Just for him, I did in fact apply for a university course in economics, but made sure during the necessary interview to appear that I had virtually no idea about the subject. I then applied for the photography course and was accepted.

Jens Pepper: So your parents were like all others in the world. They wanted you to become a respectable person with a decent job. But they had to accept, that you were about to become a photographer. What did they say when you finally ended up in Warsaw behind the iron curtain? Was this an even bigger shock for them?

Chris Niedenthal: As to what my parents thought about me being behind the Iron Curtain – I was lucky. In the post-war Polonia community in London there were some parents who refused to visit, or even let their children visit Poland in the 60s and even 70s. They said that that would only happen when Poland became free of communism. Something, of course, that nobody really expected to happen any time soon. My parents were easier-going regarding visits to Poland. Their first visit – with my sister and myself – was in 1963; they had waited for Stalin to die, and then waited a few years more. After that year, I started spending most of my summer holidays in Poland, and they came too, quite a few times. So when I told them I was trying to go to Poland for a somewhat longer time in 1973, they did not appear to have a problem with that. I guess that they never expected that I would stay there for much longer! Nobody in their right mind would want to do that, was the common feeling then.

They must have realised that my wanting to be a photographer was not the best idea for a steady job. But they never tried to stop me from going. As I mentioned before, my Father was not particularly happy about my choice of profession; as a pre-war prosecutor, he was a serious man, and had little artistic flair in him. But at no point did he try to make me change my mind. What they thought about my choice after the first six months after I had gone, then a year and so on – I have no idea. They never, ever said “come back to London, son”, and I love them for that. I would not be surprised if they had indeed thought it a bit odd that I was living in their old country that was governed by communists, and where they no longer could, or wanted to live. But strict as they were, or at least as my Father was, they never said a word.

Jens Pepper: What were the first photos in Poland that earned you money? And how and to whom did you first try to sell your photos in order to earn a living?

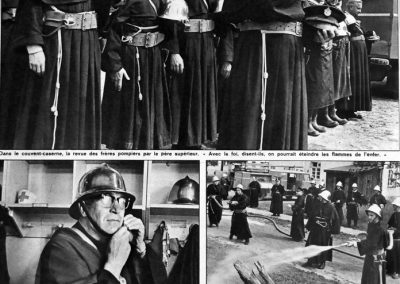

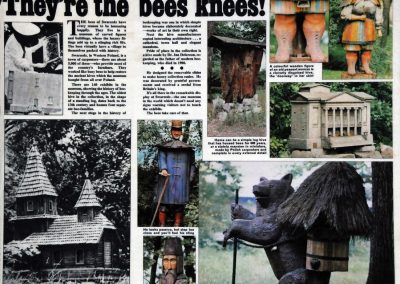

Chris Niedenthal: After finishing college, I was offered the job of a general dogsbody in a small London agency, Features International. As the name implies, it was not a news agency, but one producing and selling so-called features, or interesting, colourful little stories of no great value but that the colour press all over the world liked in the 1970s. The agency was owned in part by one of my favourite tutors at college, and he immediately offered me the job when I got my diploma. When I went to Poland, I was hoping to sell whatever material I could think up, through them. The first photo story I shot for them in Poland (actually while I was in my last year at college, so I was in Poland on holiday then) was one about an outdoor beehive museum in Swarzedz, near the city of Poznan. Sounds silly, doesn’t it!? But it sold worldwide. They had lovely old beehives, in the forms of famous buildings or animals, so it always made a nice colour spread in various magazines. The first sale was, I think, to the Observer Magazine in London, then to something called TITBITS, a somewhat more downmarket magazine. Then, when I was already living in Warsaw I remember shooting my favourite story about a monks’ fire brigade in Niepokalanow monastery. This was a prewar establishment that ran a Catholic publishing house, so with all the paper, inks and machines there, they needed a fire brigade. That was really a lovely story that I personally sold to Paris Match during a visit to France, and then the London agency took my photographs and again, sold them worldwide. Can you imagine all these monks – in their black habits – running around in prewar firemans’ helmets, with big axes on a wide leather belt around their stomachs…. Another good story was the famous salt mine in Wieliczka, near Krakow. Again, a wonderful and most interesting place. And that story sold pretty well too.

Jens Pepper: What camera did you use at that time?

Chris Niedenthal: Ever since my last year at college, I was a Nikon man. First it was a simple Nikon F, then I bought the Photomic prism with lightmeter. I later added a somewhat cheaper Nikkormat (though I had the Japanese version that was called the Nikomat. So those were the two cameras I used for my first years in Poland. Later came the FE, then the FE2, and also an FM, usually with winders (early motordrives). Next came the beautiful Nikon F3 with motordrive, and later the F4. I always used a separate lightmeter, never trusting the camera meters when shooting on colour slide film. At first I had the British Weston Master meter, but eventually graduated to the Minolta Flashmeters.

Jens Pepper: Where did you get your film material between 1973 and 1989?

Chris Niedenthal: Film material……that was always a problem living behind the Iron Curtain. You could not just go into a shop and buy good Kodak films – either colour or black and white – off the shelf. In Poland all you could get were East German Orwo or Polish Foton films. The black and white ones were perhaps bearable, but the colour ones were a disaster. Kodak or Agfa films could sometimes be bought in so-called “komis” shops – these were shops that sold assorted goods brought in privately from the West. But the prices were usually astronomical, simply because they were based on the black market exchange rate for dollars, pounds or deutsche marks. And that was many times higher than the official exchange rate. Also, one could never be sure how and where such films had been kept, and for how long. Professional films should have been stored in refrigerators, but this was of course impossible. I was luckier in that, having a British passport and a Polish multi-entry visa, I could always go to West Berlin or even London to stock up on film, but of course that was not a trip you could do just at the drop of a hat. This stopped being a problem when I started working for Newsweek, and later for TIME. Then, I could just send a telex (anyone remember telexes?) to New York requesting say, 60 rolls of Kodak Ektachrome 200 ASA and 40 rolls Ektachrome 400ASA, and in a couple of days this could picked up at the cargo terminal at Warsaw airport, having been sent there by air freight. No questions asked. For the big American magazines, film was the cheapest part of a photographer’s expenses.

So, to answer the question properly: in 1973 until I started to work full-time for Newsweek in, say 1979-80, I had to buy my own films usually in West Berlin or London. After 1980 and until at least 1989 my films all came from New York, courtesy of Newsweek and later TIME.

Jens Pepper: Did you develop the films yourself, or was it done by some laboratory in Warsaw or elsewhere?

Chris Niedenthal: In the 1970s I often used to develop black and white films myself; I even rented a primitive darkroom for some time. I never developed colour films myself. For Kodak colour slide films, the state-run Central Photographic Agency (CAF) in Warsaw had a processing lab, first for the Kodak E-4 process and later for the E-6. So my colour slides could be processed there. However, they often had some sort of technical problems resulting in various colour casts. It could be blue, or magenta, or whatever. A bit like Picasso’s colour periods. So one never knew how the films were going to come out. When I no longer had my own b/w darkroom, I used to have prints made by a girl who worked in the Communist Party newspaper, Trybuna Ludu. She was always happy to earn some extra cash.

On the other hand, once I started working for the American press, I had to ship my films (by air freight) undeveloped. They insisted on doing the processing in their own trusted labs in New York. Or if the films were Kodachromes, then they had to go to Kodak somewhere in the States. Their insistence on getting unprocessed film was understandable: their labs were better, and by getting the films undeveloped, they knew that they would be the first magazine to have that particular material. Such exclusivity was very important to them, as competition between TIME, Newsweek and US News & World Report was very intense.

Jens Pepper: When you gave away the undeveloped film rolls, you also gave away the control of the images. Did you have any influence on the picture selection for a story?

Another question I have is about the ownership of the images. Did you get the slides or negatives back or were they kept at the magazines archives? Who was and who is the owner of all this material?

Chris Niedenthal: I had absolutely no influence on the selection of my photographs for a story in either Newsweek or TIME. In reality, I had no idea whatsoever as to what my photographs were like after shooting them and then sending off the undeveloped films. I had no idea whether my exposures were correct, whether I was focussing correctly, or even whether my photographs were good or bad. I could only see what was later published in the magazines. I did, however, try to write the best possible captions for the films before shipping them off to the US. I knew very well that the picture editors in New York had very little idea as to what exactly I was shooting, in terms of the classical „who, what, where, and when” details. So I made sure that I included as much information as possible on our special caption envelopes into which we put our undeveloped films. That way they at least knew what they were getting.

As to ownership of the slides and negatives. The American system was very good: everything you shot, no matter who – and how much – had paid the expenses, the ownership of the images belonged to the photographer. If any photograph made the cover of the magazine, then they had slightly more rights to the image. Otherwise, everything belonged to the photographer. The magazines could, however, hold on to some of the photographs to keep in their archives, and would then pay you again if they were used. This was especially well developed at TIME Magazine, with the TIME-LIFE Picture Collection, so everything worked well. The rest of my material would be sent back to me, though during martial law in Poland I begged them not to send them back to me in Warsaw as they could be confiscated by the authorities. Instead, I asked that they send them to my Mother in London who, I am sure, was eventually not too happy to receive big boxes of slides, with nowhere to keep them!

However, I also had an arrangement with the Black Star agency in New York, that they would get the remains of my photographs and could sell them around the world. That seemed to work pretty well too.

Eventually, when I was no longer working for the big magazines, I asked that everything they had be returned to me, and that is what happened. So I have the original slides, and I am the owner of all the images.

The end result of all this is, that after all those years of not seeing my work after shooting it and sending it off, I am not a very good editor of my own work. Because I never really had to do it, I find it difficult to choose my pictures. Perhaps this is true of all photographers, or at least of news photographers, but I do think that the lack of seeing my photographs immediately has affected my ability to choose well. So I am quite happy to let others choose for me, for example when I am preparing a book.

Jens Pepper: Did you have more and maybe even more serious encounters with the police and the secret police after having started to work for the big political magazines in the US, especially during the time of martial law?

Chris Niedenthal: I think all of us foreign correspondents accredited in Poland, knew very well that we were being watched in some way or another. The secret police knew what we looked like; they knew where we lived, and probably knew lots of different snippets of information about our lives. If we knew that a demonstration was being planned, during martial law and afterwards too – they knew that information too of course. So, I could be idly walking around in the area where the demo was planned, maybe an hour or so ahead of time, and some secret policemen would come up to me and ask for my documents, after which they would tell me to leave the area. On other occasions, they would simply gather all the foreign journalists, photographers and TV crews off the streets even before the demo had started, and would cart us all off to the nearest police station where we would have to sit out the demo in a cramped room. Outside the “Wujek” coalmine in Katowice, where several miners were killed in the first days of martial law, I was stopped by militiamen as soon as I took out my camera – this was several months after the massacre – and was driven off to the main police station in the city where I was held for 3 or 4 hours and questioned by a typical good policeman/bad policeman duo – and then freed. With hindsight, I can now see that they treated us foreign journalists much more “delicately” than anybody else. They were quite happy to frighten us a bit, threaten us a bit – but I knew that Polish photographers caught in such situations, and who had no official backing from state media, could be held for 48hrs, have their cameras and film confiscated and end up being in deep trouble. The police who stopped me always demanded I give them the films I had shot, so in time I developed a habit of hiding the important rolls of film in an out-of-the-way pocket, but would have several special films in another pocket that I would give them. They were special in the sense that they either had nothing on them, or just some useless shots of anything that I had passed on the street that day. Because they would have to waste time processing them, I knew that they were happy enough to take what I gave them. I don’t think they ever tried to pat me down or thoroughly search my bag.

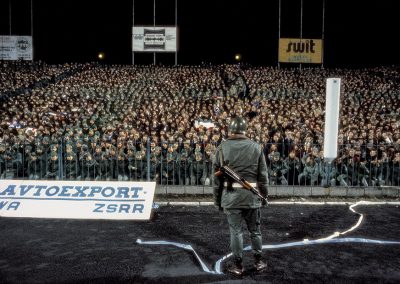

Photographing demos was always difficult for us during and after martial law. If you were on the street with the demonstrators, nobody liked you – you could be attacked from all sides. The demonstrators, if they didn’t know you, would be highly suspicious of anybody with a camera. The secret police who in all probability were also mingling in the crowd, could easily single you out and pull you into a doorway and cause you a bit of trouble. And of course the ZOMO riot police, if they saw you, would try and get you straightaway. And that could be painful. So if possible, I must admit that I usually tried high positions, meaning photographing from windows.

A few years ago I applied for and received my secret police dossier, and was rather saddened by the fact that it had very little information about me, if any at all, during martial law. I can see now that they must have been busier with other people and problems, so it looks as though they left us alone during those nasty times. When I picked up the document, I was rather amused when I saw the cryptonim the secret police had given me when they started a file on me in the mid 1970s. They called me “Kret“, that in Polish means „The Mole“. I liked that!

Jens Pepper: You told me how you got hold of film material, but how did you manage to get the exposed film rolls out of the country, especially during martial law times?

Chris Niedenthal: As an accredited foreign correspondent, I usually had no problem getting my films out to New York or wherever. With a little bit of paperwork, one could just go to the cargo terminal at the airport and put the film packet, as air freight, onto the next flight to New York. There were not that many direct flights to America then, so I often put the packet onto a Lufthansa flight to Frankfurt, from where it would be put on the next flight to JFK. Another good route was via London or Paris, as in those days the supersonic Concorde still flew. So from either of those two cities the films would get to New York very quickly. The magazines used to close their editions on the Friday night, US time, so that was always our deadline for getting the films to the Picture Desk.

Martial Law, imposed in December 1981, was a different problem altogether. Poland was suddenly cut off from the world on December 13th. No telephones, no telexes, no flights. How to get my films out, then? Photography on the streets was forbidden at the beginning of martial law, so shooting anything at all was problem Number One. Number Two, an even bigger problem, was getting the films out. Sure, I could just jump in my car and drive to West Berlin. But would I be able to get back into Poland afterwards? Petrol was rationed then too, so would I be able to drive all the way to Germany? How would the Polish and East German border guards react to a journalist leaving the country; what materials would he be carrying? Even if the Polish guards would let me through, the East German guards were even worse, and could cause me trouble. Trains were still running, so I decided that that was the only relatively safe way out – but, not wanting to leave the country myself then, I would have to find a passenger willing to take the risk of smuggling out some films. Not easy! I got to the station in time for the evening train to West Berlin, but there were, quite naturally, not many passengers and the ones I did approach refused to help. The train was about to leave in a few minutes so, in desperation I jumped into it and ran through the compartments. And suddenly I came across a young West German student who agreed to help. I gave him the packet of films (10 rolls, if I remember correctly), plus a note with the telephone number of the Newsweek bureau in Bonn. Call them when you get home – and they’ll do the rest, I told him. Now everything was in the hands of the gods. Would he get out of the country without being searched? Would he phone Newsweek when he got home? Or would he get out OK, and then just sell the films to Stern Magazine or whatever, and that would be it. I know, it is not very nice to suspect things like that, but who knew then what could happen? Anyway, it turned out that everything worked. He was a wonderful guy – did everything perfectly. He got home, somewhere at the other end of West Germany, called Newsweek in Bonn, they sent a motorcycle courier across the country to him – and everything reached New York in time.

I just wish I had made a note of his name or even just the place where he lived. I would love to thank him for what he did, all those years ago. Thank you, young German student!!

Jens Pepper: So you had problems to get films out of the country during martial law period. How much less film were you able to send abroad in comparison to former times? And I add this question right away. When the officials did not want you to photograph demonstrations and the like and to send your photos to magazines in the US etc., why did they allow you to pick up the films which were sent to you at the airport? They obviously new about your work, wanted to obstruct it, but still let you have all the working material? That is somehow schizophrenic, isn’t it?

Chris Niedenthal: It’s difficult to say whether I sent out fewer films during martial law than in normal times. I remember that the first packet that went via the West German student, was 10 rolls, then a few days later a few more, and so on. Please bear in mind that these were not normal working conditions, so my usual level of about 10 films per working day could not be upheld. As to the officials not wanting me to photograph demos and such things, then I can only say that as a group, the accredited foreign correspondents living and working in Poland were a “known entity” for the authorities – meaning that they knew about us, kept an eye on us, but did not necessarily obstruct us. I say this now, with hindsight; at the time, I don’t remember thinking that way. I think they basically turned a blind eye onto whatever it was we were doing. But again, I can say that today. If they had really wanted to control our work, they could have demanded that all films be processed in Poland, and that we could only send out processed films that had been checked by them. But I doubt if they even thought of that, and could not have been bothered about it if they had. Perhaps, if martial law had been imposed in East Germany, or in say, Romania, then maybe the Stasi or the Securitate would have demanded that. They were far more ruthless. But Poles, it appears, can be somewhat more laid back when it comes to rules and regulations, and certainly so when it comes to carrying them out. So schizophrenic – no. Just lazy, perhaps!!!

Jens Pepper: You mentioned that you sometimes did not see your published photos for years. Newsweek etc. did not send you copies of their magazine to your address? Or did you not want to have the magazines to be sent to you, so you would not get into trouble? But the secret police knew about your work, so it would not have made any difference, would it?

Chris Niedenthal: I did not see my processed films for years – not my published work. The latest editions of Newsweek, and later on TIME Magazine, were always shipped in to the Warsaw bureau every week. The only exception was the first few weeks of martial law when we all had to keep a low profile and anyway, all flights to and from the country had been cancelled. So whatever was published in the magazines I could see pretty fast – except, as I said, during the first weeks of martial law.

Jens Pepper: Was it entirely your choice what you were going to photograph for Newsweek and Time or did they ask you to do certain stories? Or was it a mix of both? What about the travels to East Germany, Russia, Czechoslovakia and the like; were these commissioned assignments?

Chris Niedenthal: After the ground-breaking strike in the Lenin Shipyard in Gdansk in August 1980 I think I could say that I was given carte-blanche by Newsweek to photograph “anything that moves” so to speak! Communications between Warsaw and New York were a pain, it was difficult to call them on the phone, and we mainly used telexes to keep in touch. But that was not a machine one had at home, so even with that there was always a time delay between getting messages and answering them. So I just had to keep my ear to the ground to keep up with everything that was happening in Poland then, and then I could just shoot what I thought was worth shooting. Meaning everything, in fact! Just getting hold of information was not that easy, as of course we had no mobile phones then, telephones were often tapped by the secret police, there was no internet, Facebook or anything like that. So human contact was the only way to find out anything. And, may I add, what a great aid human contact is! I had a network of friends and colleagues working for the foreign press to whom I would go to find out the latest news. A simple, if time-consuming system – but it worked. Also, most of the western foreign journalists here had these little Sony short-wave radio receivers so that we could listen to the BBC World Service or whatever. It was quite funny really: in a restaurant or on a street corner, all the journalists would suddenly stop what they were doing when the news services came on every hour. So, for example it was 6pm in the evening and suddenly all the radios would be whipped out of bags or pockets, and all you could hear were the famous tones of the BBC…. They always seemed to know what was happening. Ah, those were the days!

So, to answer your question: during the heady days of late 1980 and most of 1981, I would shoot everything I could for Newsweek – no questions asked. Later, working for TIME Magazine from 1985, I became their photographer covering Poland, Eastern Europe, the Balkans and a few years later, the Soviet Union as well. Stories in these countries were coordinated with the correspondent, who at first lived in Warsaw, and then in Vienna where TIME Magazine had its Eastern European Bureau. So stories in Poland, Czechoslovakia, Hungary, Romania, Bulgaria, Yugoslavia were all done with the TIME journalist. East Germany was not actually covered by this bureau, so for TIME Magazine I only got in there in October 1989, when the GDR celebrated its 40th anniversary. A month before The Wall came down!. But I did manage to spend some time in East Germany in 1984, when Geo Magazin in Hamburg asked me to help out with a special edition they were planning on that country. They had trouble getting their own photographers in there, so they asked me whether I could try to get in on my own. And I did. Most interesting! As for the Soviet Union, then that was also not part of the Eastern Europe bureau’s territory. Moscow had it’s own TIME bureau, and I worked according to what they were planning to do. And that meant that I could spend a lot of time there, for several weeks at a time, because getting a western photographer in there was always a problem, but I was accredited there as a foreign correspondent and had a multi-entry visa.

Jens Pepper: Tell me about your prize winning photo of János Kádár.

Chris Niedenthal: My photograph of Hungarian communist leader Janos Kadar was my first (and in fact, only) assigned cover photo for the European edition of TIME Magazine.

In 1986 the magazine was planning to do a special cover story on Hungary, and its specific version of what the West called “Goulash Communism”, so they sent their Editor-in-Chief plus their correspondent to Budapest to cover the story and hold an interview with Janos Kadar. I went along for the ride, photographing whatever was necessary for the story, and was also present at the interview.

Shooting photos during interviews is only good if you just want a “talking head” sort of photo. The editors, however, wanted a more formal portrait. During their talk with the Hungarian leader, he told them that his favourite painting was one that hung in his office and showed Lenin playing chess. They asked me to go back to Budapest and photograph the man with that particular painting.

So I did. Not having portable studio lighting at the time, I borrowed an outfit from a Polish friend and flew to Budapest. When I was let into Kadar’s office I saw that the painting was hung relatively high up, and I knew that Kadar was not particularly tall. I decided to opt for a lighting set-up typical for photographing paintings, i.e. equal lighting from both sides, so that the painting would be well-lit. Kadar was then led into the room, and I tried to place him in a position below the painting that showed both him and the artwork. Not easy – he was not tall enough. I had no ladder with me, and his assistants didn’t have anything like that either, so I begged them to bring me something he could safely stand on. What they came up with surprised me, as I was in an atheist, communist office and they brought me something that looked suspiciously like a prayer kneeler! I asked Mr Kadar to stand on that, which was not that easy as he was an elderly person and was probably frightened of toppling over. Still, he stood bravely on it, and I shot off a roll of film. Each shot was almost identical to the first – he never changed his expression. He was nervous, and I was nervous, so i did not see then that he was slightly sweating, with the damp showing beneath his eyes. I should have asked him to pull out his handkerchief and wipe his face. But I did not think of it then.

And that was it. One roll of film, thank you, goodbye.

When TIME received the film they saw the damp patches under his eyes and laughingly said that they looked like tears and that he was crying for his sins as the so-called “Butcher of Budapest” in 1956. Still, when they ran the photo on the cover, the “tears” had been retouched.

I had no idea that TIME had entered the portrait into the World Press Photo competition, so I was rather surprised when I suddenly got a telegram in 1987, notifying me that I had won a prize in the competition. My first reaction was “Really? For what?”. Still, it was a very pleasant surprise!

Jens Pepper: Another important photo in your career is the one with the armored military vehicle in front of a Warsaw movie theater on the day in 1981 martial law was declared in Poland. On the outside of the building you see the advertising for the film that was just presented in this cinema: Apocalypse Now by Francis Ford Coppola. This photo became quite iconic. And how important it still is could be seen only a few days ago when the reigning PiS government misused this photo without your permission for an event organized on the occasion of the 35 anniversary of the declaration of martial law during the Peoples Republic. What does this photo mean to you and why is it so important for you that the present Polish government does not use it against your will?

Chris Niedenthal: This – as you call it – “iconic” – photograph was of course pure luck, as is usually the case with such images. It was really a simple case of putting two and two together, in the flash of a second. A bit of wordplay, a bit of symbolism, and realising that whatever else I was going to shoot that day, I had to take this photograph. In the end it was a simple case of finding a staircase with a window looking out over the street, in order to avoid knocking on peoples’ doors to ask if one could shoot from their windows. In that area of Warsaw where the Moscow Cinema stood, one could never be sure who lived there as the feared Interior Ministry was just around the corner. I could not photograph from street level, as this was forbidden from Day One of martial law. It had to be a window shot, and of course the photo is better because of that – the angle is just right and the perspective from above puts everything in the right place in the right order. The name of the cinema that shows what the Poles thought of Moscow and the USSR then; the name of the film, Apocalypse Now (Czas Apokalipsy in Polish) and of course the APC, armoured personnel carrier with soldiers milling around it. Perfect. Martial law in a nutshell! The photo means a lot to me of course, as for the Poles it has become the symbol of that dark period starting in December 1981. And it’s a good feeling to have at least one good photograph under my belt!

As to the present government using this, or in fact any of my photographs for any of their own purposes, is for me a complete no-no. Considering what I think of these people, I have no intention of allowing them to come anywhere near my photographs! Their view of the world is so different from my view, that it would be difficult for our ideological paths to cross. Their office in Opole wanted to use this photograph for an invitation and poster relating to ceremonies commemorating the start of martial law 35 years ago, under the patronage of a young deputy Justice Minister who, as far as I’m concerned, is not the ideal choice to hold such a high position. And that made my hair stand on end. They didn’t bother to ask my, or my agency’s permission to use the photograph, so I put out a statement that this was unlawful and that I had no intention of allowing any present government office to use any of my photographs. I was pleased to see that the media buzz around this made the young minister withdraw his patronage from the event – so that was a good thing. Contrary to media reports that someone would apologise to me – no one has in fact done so. From newspaper reports I heard two rather curious excuses made by the office worker in Opole who had used my photograph: a). that because the photograph had been used so many times over the years, that it was OK to use it without permission or even payment, and b). that anyway, she had made no money herself by using this photo, so what was all the fuss about? By the way, the name of the political party is Law & Justice. Apart from all that, there was no official reaction from PiS – but neither did I expect any. The word “sorry” is not, I suspect, in their vocabulary.

Jens Pepper: During your career you met some important people of recent Polish history. Which encounters were the most impressive to you? How did you get along with Lech Walesa?

Chris Niedenthal: I would say that every news photographer worth his salt ends up meeting important people during his career. In your question you mention Lech Walesa and yes, I guess he was the person who made the strongest impression on me, perhaps because I was fortunate enough to have met him at the very start of his public life. That was the second day of the strike in the Lenin Shipyard in August 1980, and I managed to see his negotiation skills that very day when he was talking to the shipyard director, not to the high-powered Party officials who came soon afterwards. I guess I felt a soft spot for him ever since then. I visited him quite often later on, in his family apartment in Gdansk, and, like all of the foreign press, was on first name terms with him. But did I get to know him closely? No, not at all – I was always careful not to get too close to anybody then, neither dissidents, politicians, nor diplomats. I was always aware that as a journalist I had to keep a neutral distance away from the people I was covering. My friends would argue that that was just my British upbringing, staying aloof from everybody, but I would argue with that! Whenever we meet, he always has some comment up his sleeve, the most memorable one being when I photographed him during the Winter Olympics in Salt Lake City when he turned to me and said: „You are not developing at all; I was an electrician, a strike leader, then a union leader, and President of Poland – yet all you do is take photographs!”. He was right. I liked him for that!

Pope John Paul II was also most impressive, on a very different level but, though I photographed him many times, I never had a one-on-one with him. But I loved his face – that sense of intelligence, friendliness, goodwill and that fatherly smile….

Poland’s first woman premier, Hanna Suchocka also made a very positive impression on me, though I never photographed her when she was the Prime Minister. I caught up with her later, in Rome when she was Poland’s ambassador to the Vatican, spending several days with her on a photo shoot.

Tadeusz Mazowiecki, Poland’s first non-Communist Prime Minister was also a very charming, though unassuming man but again, what can I say when I am given half an hour to spend with a busy man who would really be very glad to see the back of you because he has more important things to do. Being somewhat unsure of himself on a visual level, Mazowiecki had a quirk that caused havoc during a quick shoot because he would always roll his eyes upwards, and then, as if to make up for that, look downwards, Try shooting a quick portrait!

Jens Pepper: Looking back we can laugh, but I can imagine that you got quite nervous in a situation like the one with Mazowiecki about getting a good photo for the magazines.

Tell me, how did you experience the change of the political system in Poland and how did this influence your work?

Chris Niedenthal: Sure, we can all laugh about such situations while photographing busy politicians – but there is always the aspect of working up a nervous sweat while waiting for such a shoot to happen. You just never know which way things will go. I can well remember the time when I was supposed to have a quick photo session with West German Chancellor Helmut Kohl, who infuriated me (not an easy thing to do, may I add!) by making me wait several hours before I could shoot photos of him. Add to that his lack of English and my lack of German did not make matters any easier.

As to feeling the change in Poland’s political system in 1989: that is actually hard to describe right now, probably because I was so busy covering everything else in Eastern Europe at the time or just afterwards. Poland’s big jump set the ball rolling – Hungary, East Germany, Czechoslovakia, Bulgaria, Romania plus things happening in the Baltic states. I was extra busy that year, in fact, looking back at all my work from 1989 I can hardly believe I managed to cover and shoot so much then. Also, at that point I was still working from a Vienna base, so I was not in Poland all of the time. But I remember that what started to happen was that from a purely political story, the story turned into more of an economic story, so one had to shoot photos of all the street vendors and so on. Not all that interesting, really. And a bit later this turned into more of a business story, with private people starting businesses, making fortunes etc. Again, for me that was also not very interesting. And please remember that by the time it was East Germany’s turn to collapse in November 1989, I was standing under the Berlin Wall and in effect feeling that the rug was being pulled out from under my feet – meaning that since things had gone so far and the end of the GDR was beckoning, then I realised that my work for TIME magazine covering communism would be coming to an end. As it turned out, I still had a few more years with them but, as I mentioned before, the story was no longer so passionately interesting for me and I knew that sooner rather than later, this part of my work would end. Eventually it did end, and that of course opened a big void in my life, especially as I was still feeling the effects of being mentally burnt-out (did I ever mention that being a hard-working international news photographer is an exhausting job?) after the 1989 marathon. Luckily I teamed up with Der Spiegel for a few more years, so this somewhat cushioned my departure from photographing communism.

Jens Pepper: Did you stay in the news business or did you start to work on other aspects of photography?

Chris Niedenthal: Apart from what I shot for Der Spiegel in the early 90s, I did not do much in the way of news photography anymore. As a full freelance once again (I had been a contract photographer for TIME magazine, so I could not work for Newsweek at the same time) I could now accept assignments from both magazines, and that sometimes happened. But basically, by the mid 1990s I had run out of steam regarding strict news photography. I worked a bit for some of the new Polish magazines, and then was approached by an old colleague who had fled Poland in the 1980s and had run a small studio in Sweden. He felt the time was ripe to return to Poland and wanted a partner to open a studio in Warsaw – commercial and advertising photography. I said OK, let’s do it – though I had never been a studio photographer before except for my college days in London. We managed to rent an old, very big apartment in central Warsaw and set to work renovating it to meet the needs of a photographic studio. We put a lot of heart and soul – and hard work – into getting it ready, and for the next six years we tried to make a living as commercial photographers. For me that was no easy task, as for a photojournalist to be cooped up in a studio from 10am to 6pm was a very difficult, though certainly interesting, thing to do. I don’t know about our photography, but we became famous for our parties! We came up with a wonderful idea: One-night exhibitions of the unknown work of well-known people. If you weren’t invited, or you couldn’t make it that night – you never saw it. We persuaded quite a few famous people, rock stars, writers, singers, actors all of whom had their little, largely unknown hobbies on the side. They could show whatever they wanted, and our guests loved it! The press usually ran stories on these gatherings, and once we even had an honoured German guest, your present President, Joachim Gauck who, I must admit, was not President at the time!

So yes, we had a good time, we didn’t make all that much money, but it was all a great experience for me – to try and create photographs rather than just document what I saw before my eyes. As I said before – no easy task! I left to go my own way after 6 years, but have great memories of the time spent with my colleague.

Jens Pepper: You were very much photographing the demonstrations against the politics of the PiS government recently including the occupation of the Sejm (the protesters outside the parliament supporting the politicians inside). All over Europe you can see movement toward a new nationalism and toward protectionism, the raise of intolerance and more. Is the time getting more interesting again for a news photographer like you in these days?

Chris Niedenthal: Well, yes, I guess photographers should be getting ready to follow and cover the new wave of “The Force of Darkness” that seems to be enveloping more and more countries including, though we have to wait and see, the USA.

I cover whatever is happening here as much as I can, though really it is just for myself as I no longer have any outlet for my news pictures. I do sometimes pass them on to the Forum Agency here in Warsaw, as they represent my work, but I am neither as fast or as agile as their own photographers who cover the same events. So I do it to satisfy my personal need to carry on documenting life in this part of the world, or at least in Poland. I have done it for so long now, that I find it difficult to stop. And the second reason is that I am actually furious that the Poles have allowed themselves to be duped into voting into power a rightwing government that is getting closer and closer to doing what the communists used to do. Why they want to destroy all the good work that was done by their predecessors, I just don’t know. Of course not everything was good, but is it perfect anywhere? Their “idee fixe” appears to be a potent mixture of hatred and revenge; hatred towards all who don’t think the way they do, and revenge for all the lost elections they had before. Hardly a praiseworthy way to rule a country! They have successfully divided the country into two distinct political camps, but at the cost of demolishing virtually all national institutions. In addition, their actions and specific way of working means that Poland has lost virtually all the hard-earned standing and respect it had gained in the European Union over the previous years. So yes, while I would be happy to lead a somewhat calmer and easier life now, when I am no longer in my 30s or even 40s – I can see that there will be work to be done. I’m actually very moved when, during demos and rallies, people seem to recognise me and come up to me to shake my hand and thank me for all my work over the years, and to thank me for being with them once again! Photographers are usually anonymous, so this is actually a warm feeling, I must admit!

Jens Pepper: You told me that you are working on your archive. How big is it and is this a satisfying task after a long working life to see again what you have achieved?

Chris Niedenthal: My main work over the past few years has been to try and organise my photographic archive. But when I say “my” work I actually mean that of my amazing assistant, Julia, who knows how to do it – whereas I don’t. That’s because I belong to a small group of photographers who rarely managed to see what they had shot. Shipping undeveloped films to New York meant that I only saw what was published. Sometimes the colour slides were returned to me at my home address relatively quickly but even then I usually had no time to look at them because I was away on another assignment. So the unopened boxes of slides got piled up somewhere, taking space – a situation much-unloved by wives anywhere! During and after martial law I asked that my work be sent to my Mother in London, for safety’s sake, so then she, poor Lady, was soon inundated with boxes of slides piled under her bed, in her cupboards and so on. A situation much-unloved by mothers anywhere! The end result was that my basement in my present house in Warsaw became clogged with cartons full of little boxes full of slides. On hearing the loving words of my wife cooing in my ear “When you die, I’m going to throw all this out”, I decided that something had to be done. I couldn’t do it myself – I would wade into the basement, open a random box, look at some slides and say „Wow, I remember that! Did I really shoot that?” and then, not really knowing what to do next, I would put the slides back in the box and leave the room. So Julia is systematically looking through everything, not throwing anything away, putting slides into sleeves of 20 and then into filing cabinets. I always reckon there must me at least half a million slides and negatives in the archive. It must be something around that, probably much more. On a typical day of shooting I would usually use 10 films. If I worked, say, 100 days a year, that makes 1000 films, 36000 frames a year, remembering that each film had 36 shots on it. Over 10 years that would be 360000 pictures. Those were the high intensity years of course, and seeing as I have worked for more than 10 years, there should be a lot more images. But really, what’s the point of counting, as a large proportion of all those pix is junk or close to junk. Out of focus, moved, over or under exposed. Slide material was difficult to use, you had to be near-enough spot on with the exposure. Compared to today’s digital material and equipment, sensitivity was low, so in bad lighting conditions you would be in trouble and flash was disliked and rarely an option. And just think how many pictures photographers can shoot today, with the possibility of holding thousands of high resolution images on a small memory chip…..

But it actually is a wonderful feeling when you look at some of your old material, never before seen by you, and the memories come flooding back. This is what has been happening to me these past few months when I decided I would try to make a book out of my photos shot in the magical year of 1989. That really was an incredible year, not just for me but for all of Europe – and looking through the pictures I find it hard to believe I had time to shoot all that, in all those places, in all those countries virtually day in, day out, week after week, month after month. And just think of the luck I had, or hard-earned journalistic instinct, call it what you will – for example on November 9th 1989 when the Berlin Wall started to come down I was in Warsaw, covering Chancellor Kohl’s official visit to Poland when, in the evening news came of what was happening around the Brandenburg Gate in Berlin. Sure, I was as surprised as anybody. But, for some unknown reason, prophetic vision or whatever, in my pocket I had an air ticket for the 7am Interflug flight to East Berlin the next morning, so by 8-9am I was happily photographing everything I could see on the border between Berlin-Schönefeld airport and West Berlin, and a bit later in West Berlin itself. There were no other journalists on that flight, and Chancellor Kohl himself only managed to get back to Germany hours later. I mean, I’m no genius – but that day I was pretty pleased with myself. And my photo ran on the TIME magazine cover, worldwide. And that’s what photojournalists like!

Jens Pepper: Bosz recently published a huge book with lots of your photos. Your autobiography was also published in Polish (I hope it will be translated into English one day!) How importandt are books for you?

Chris Niedenthal: The Polish publisher BOSZ published my book of selected photographs 1973-1989 in 2014, and it is now in in its second printing. They also published my first major book 10 years earlier. And now we are planning a possible book about the incredible year of 1989 itself. And in 2011 the Marginesy publishing house came out with my autobiography, though I always find it embarrassing to admit to having written a book about myself. So my answer to your question about the importance books have for me – has to be yes, I place great importance in books. Meaning, of course, that I love coming out with books that are full of my photographs! In today’s world, this is what photojournalism is all about. Before, I was happy to be published in magazines all over the world. News magazines back in those days were important, people waited for them to appear on newsstands, usually on Mondays. TIME, Newsweek, Der Spiegel, Paris Match, Stern – these all used to be vital sources of intelligent information. With the advent of 24hr television news channels, and especially the rise of the internet, all that has changed. So the news magazines have changed, rarely for the better. To cut costs, they rarely send out photographers across the world at the drop of a hat. But there are concerned photographers everywhere who are very good, are willing to work, have great ideas, often find interesting ways of financing their dream stories – and where can they show their work? Sure, magazines will still sometimes run them, but the other outlets are books, galleries and so on. Not easy, but it can be done. So even though I had the honour of working for the big magazines towards the the end of the golden era of photojournalists – I must admit I enjoy the prestige of having books of my photographs published, if only for the purpose of documenting history. Because we, as photojournalists do just that. Without really realising it, we live and breathe history. We are there when things happen. Sometimes small things. Sometimes big things. And so I am proud to have been in most places when and where history was happening before my eyes throughout the 1980s. Those pictures had, to a certain extent, less meaning soon afterwards than they have now, 25, 30 years later. The photographs have aged of course, but they have also matured. And this is the moment when we turn into visual historians.

Jens Pepper: Who are the most interesting contemporary Polish news photographers in your eyes? And are you in touch with them?

Chris Niedenthal: I know several of the young, aspiring Polish photographers, and they are good, very good. Perhaps some of them are not quite so young anymore, they are certainly not in their twenties. But for me, they show the future of what used to be called “concerned photography”, and is now something I would call intelligent, personal photojournalism. They are the leading lights, the “angry young people” who come up with their own, well-thought out projects, find some way to finance them, and then produce books and/or exhibitions to show what they have done. Sure, this is certainly not typical newspaper photography – but it doesn’t have to be. It’s a whole level higher. Wojciech Grzędziński, Maksymilian Rigamonti, Filip Ćwik, Agata Grzybowska and many more. All very focussed young people, all very good photographers. I know them partly because I wrote about them in a monthly column in, of all places, the Polish edition of the business magazine Forbes. For over a year I would choose one promising or established photographer a month, take a simple portrait of them, and then write a few words about them – and then they’d have several pages of their photographs published. This was certainly not your typical business magazine section, but the Editor came up with this idea and managed to keep it going for quite a while. He deserves a medal for that!

Chris Niederthal ist ein polnischer Fotojournalist mit britischen Wurzeln der seit Anfang der 1970er Jahre in Warchau lebt. Von dort aus hat er für viele Nachrichtenmagazine, wie Newsweek, TIME, Spiegel, Paris Match und Stern, über die ehemaligen Ostblockstaaten berichtet. Für sein Foto des Ungarischen Politikers Janos Kadar erhielt er 1986 den World Press Photo Award.