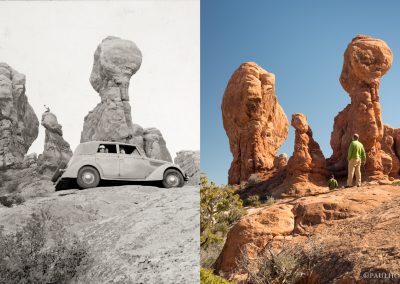

Grand Canyon at Indian Garden

Jens Pepper: It is almost exactly 25 years ago that we met in Berlin, shortly after the wall came down and only months before the German reunification took place. At that time I think you were at the beginning of your career as a photographer, doing portraits of politicians from South Dakota, the state you are still living in, in the USA. You also were doing lots of natural photos of the Black Hills, the Badlands and other beautiful and exciting sites in your State. At what point of your life did you decide to become a photographer?

Paul Horsted: That visit to Berlin was early in my career but not quite in the beginning. I began taking photographs while in high school (10th grade, at about age 16 in the year 1977). My father had been in the Army in 1955 (before I was born), and he was stationed in Germany. While he was there, he bought a Voightländer 35mm camera which he used for many years. Twenty years later, I was able to use it to take sports photos when I joined the staff of the school yearbook and newspaper. I lived in a small town called Brandon, in eastern South Dakota. There was also a small weekly newspaper there. I met the editor of this paper on the sidelines of a basketball game, and he asked me if I would be interested in taking photos for the town newspaper (in addition to my work for the school yearbook and newspaper). I was excited to get a job, and began taking all the sports photos. Eventually I also took news and feature photos for the town newspaper, and within 2 years, I also got assignments from the big-city newspaper nearby, in Sioux Falls, while I was still in high school. I had become a professional photographer without really planning to do so. All I knew was that I enjoyed taking photos, developing them in the darkroom, and seeing them published in the local newspapers with my name under them.

At that time I thought I might be a “photojournalist“ for life, but later realized there were many other types of photography, and some of these (wildlife, landscape, wedding, advertising, etc.) were important at different times in my career as I adapted to freelancing and making a living on my own as a photographer. However my time in the newspaper business taught me a lot about shooting in many different situations and settings, and in working quickly, a habit I still retain.

Jens Pepper: So this is really learning from scratch. This sounds wonderful. For how long did you work for the newspapers? The one in Sioux Falls was called the Argus Leader I think?

Paul Horsted: Yes, I learned photography from real-world experience as a newspaper photographer, not from going to a photography school, though I did take some workshops as well. I learned from more experienced photographers who worked at the Brandon Valley newspaper, and later at the Argus Leader in Sioux Falls. I also learned from my own mistakes as I would usually develop my film the same day I shot it, and could see where I did something not right.

I worked at the Brandon Valley Reporter newspaper (a weekly paper) for 3 years, from 1977 until 1979, the year I graduated from high school. I got my first assignment for the Sioux Falls Argus Leader (a daily newspaper) around 1978 while still in high school. After high school I started at university, and continued to do freelance and sports photography for the Argus Leader. I quit university a year later and started working at the Argus Leader, a few hours a week and eventually full-time when another photographer left the newspaper. I was there as a full-time photographer for about 2 years, and part-time for about 2 years before that. So I had a total of about 6 years of newspaper photography experience, including my earliest work at the weekly newspaper.

After a few years at the Argus Leader, I found myself getting tired or nearly “burned out” on working as a daily newspaper photographer. I enjoyed much of it, and gained experience shooting pictures every day of the week, but was tired of covering car accidents, house fires, drownings, and other disasters where I now feel we were intruding on people who were at their most vulnerable time. I once took a photo through the window of an ambulance! I can’t believe it now but there was some pressure to produce images no matter what the situation. I decided it was time to go back to college, at South Dakota State University in Brookings. I actually sold my camera equipment and took a year off from photography. But then someone on the university campus heard I was there, and asked me to be a photo editor for the college yearbook. It was a paying job, which helped with my college expenses and gave me entrance into every corner of the university with my new camera. From there I met other photographers, which ultimately led to the next part of my career in the South Dakota Tourism Department.

Jens Pepper: Did you know for yourself at this time of ongoing university studies in Brookings, that a life in photography would be what was laying ahead of you? Or had you been unsure about the direction of your future work life? Were there other professions that would have been of interest for you?

Paul Horsted: I was not sure I would stay in photography when I went back to university at Brookings. It sounds ignorant now, but I though newspaper photography or photojournalism was the only kind of photography I wanted to do. Getting tired of newspaper work meant I might look for a different career, or at least take a break from photography. At the university I did not study for a major at first, I did not “declare” a major as we say because I was not sure what I wanted to do. But I started general classes, and explored some other interests. I learned how to fly an airplane (though I do not have a pilot license now), took scuba diving, and studied the German language (which I had studied in high school as well), explored horticulture, writing, and social sciences courses. I finally graduated with a degree in Psychology and a minor in German, but I didn’t really think any of those would be my career path. By the time I left university I had an opportunity as a photographer at the South Dakota Tourism Department which I followed.

Jens Pepper: How did it start with the South Dakota Tourism Department and what were your tasks there?

Paul Horsted: While I was at the university, I learned about a summer internship program at the South Dakota Department of Tourism, for writers and photographers. I applied for the internship and worked there for 2 summers. It was a great time to learn. We traveled to festivals, landmarks, and other tourism destinations in South Dakota to take photos. My work was published in tourism publicity, maps, posters, and brochures. I learned about shooting color slide film (previously I had used mostly black-and-white film) and how to control exposure and light more precisely. I also began to understand there were other types of photography I might like beyond photojournalism, such as landscape, wildlife, and historic subjects. One of my favorite jobs was to help put together multi-media slide shows of my photography and that of the other photographers on our staff. Back in those days, using 35mm slide projectors, we could program 3 or even 6 or 9 projectors that would be set up in the back of a room for a large audience and then present a fast-paced slide program about our beautiful state. I still enjoy doing this kind of live presentation with my work today but of course use a laptop and Apple’s Keynote software to present my work. It is better today I think…the bulbs in those slide projectors always seemed to burn out at the wrong time!

Jens Pepper: Weren’t you also in charge of making official portraits of politicians, like the Governor of South Dakota or Tom Daschle, who at that time was in the U.S. House of Representatives for your State?

Paul Horsted: No, I wasn’t really in charge of that type of photography, and I did not consider myself a portrait photographer. I did photograph our Governor George S. Mickelson when he met with people coming to the State capitol for various causes, or when the State Legislature was in session (every January). I also occasionally covered meetings and other events where Governor Mickelson met dignitaries such as our President (the first George Bush) or other officials, but it was not a regular part of my job.

Jens Pepper: Was it at this time at the Tourism Department, that you fell in love with what might become your life time passion: landscape and nature photography?

Paul Horsted: Yes, at the Tourism Department I learned about landscape and nature photography and that experience helped me as I started my freelance career in 1990 (when I also married Camille Riner and left Pierre, SD to join her in Wisconsin before we moved to Michigan). I also took some wildlife photographs in our parks. But my photojournalism background helped me a lot, as we also took photographs at festivals and other events where people were doing interesting things such as hiking, biking, skiing, snowmobiling, etc. and even farm and ranch and other “South Dakota jobs“ activities.

Jens Pepper: Were you familiar with the work of photographers like Ansel Adams or Paul Strand at that time?

Paul Horsted: I did not have a formal photography education so unfortunately I did not recognize some of the “masters” until I started reading on my own later. I was so young, I was busy just learning from the more advanced photographers around me at the newspapers I worked for…they were my mentors. When I first started working in newspaper photography, and as I began doing some landscape work with the Tourism Department, I was impressed by photographers working for National Geographic, LIFE magazine, or other big publications, and aspired to that type of work (long ago I did have photos published by the New York Times, USA Today, and other papers, and a few times in LIFE and National Geographic publications. Then I found out it didn’t pay very well!) These days I’m more inspired by many lesser-known photographers who worked in the 1860’s-early 1900s under very difficult conditions in remote locations (at today’s National Parks here), with glass-plate negatives and lots of heavy equipment and long shutter speeds. Amazing to me is the quality of the images they produced under those conditions, and their landscape compositions which can have great depth as they were often using stereoscopic cameras and wanted to emphasize foreground to background.

Jens Pepper: How did you plan your freelance career? Did you have a clear vision of it?

Paul Horsted: I had met Camille Riner while I was working for the Tourism Department in the late 1980s, and by 1990 we had decided to marry. We agreed I would leave my job, start my own business, and follow Camille wherever she could find a teaching job after finishing her Master’s Degree. We knew one of us would need a steady paycheck! We ended up spending 8 wonderful years in Michigan, where Camille taught in the art department at Southwestern Michigan College. (She is a printmaker and graphic designer, and does all the layout/design for the books we now publish.)

I found over time that my freelance career had to adapt with the changing photography landscape and economics. Initially I thought I would do magazine and other freelance publication work. This seemed the most interesting and with the most opportunity at first. But in time I realized it simply did not pay very well, at least not enough to make a living strictly from this type of work (others might disagree, but I think all agree pay is very low in editorial work.) I learned that the exact same photo, when used for advertising, might pay 10 times or more what it would if used nearby on the editorial side of the magazine. So I began shooting “stock photography” and advertising these images in national catalogs. The phone would ring, someone would want to license my photo of Mt. Rushmore with a man hanging off Abe Lincoln’s nose for a corporate report or magazine report, we’d negotiate the price, I’d send them a color slide, and wait for the check. It wasn’t always that simple of course, but it could be very profitable…I once licensed a single photo for more than US$5000. and made more than that from several images having repeat sales over time. Those days of the pre-internet 1990s are gone! Eventually stock photography moved from print catalogs, to CD’s, then to the internet, when a glut of millions of images reduced stock photography prices to a commodity. But around this earlier time, I also landed a couple of small book deals, shooting a guide book on South Dakota and another about Custer State Park in the Black Hills. This probably helped with a later decision to produce our own books.

I should add that as a freelancer, I shot a few portraits (but never considered myself a portrait photographer), local advertising jobs, and even some weddings. My photojournalism background fit well with an emerging “candid wedding photography” movement. I didn’t really like shooting weddings, I found it very stressful, but it was paying the bills at times and the clients were happy with my work. (I even got a repeat client from a woman who asked me to shoot her second wedding after she divorced the first husband!)

I think it sounds like my focus was on money rather than art, but I wanted to stay in business of course. I did spend a lot of time learning about good business practices in photography and was never afraid to say “no” to a job where I would lose money or make very little, or to enforce my copyrights as the creator of the work. It always amazed me that many photographers would let their clients (a magazine for example) tell them how much they would pay, rather than the other way around. Editorial photography is the only industry I know of where the customer set the price (or tried to). I think my ability to say “no” is partly why I’m still in business after 25 years.

Back to the Michigan years, eventually Camille was ready to leave teaching to pursue her art, and my freelance career was stable enough that we decided to move to Custer, South Dakota, in the Black Hills (where Camille had lived in an earlier time, and a place I also knew well). It’s a beautiful mountain area and we live in a small town. We sort of fell into book publishing, which was the best move of my career as it turned out.

So no, I didn’t have a clear vision of my freelance career, I had to adapt along the way to changing conditions and am still trying to do so!

Jens Pepper: This clearly sounds like an adventuresome career and you seem to be very happy with it, which is great. You are right, magazines and newspapers mostly offer dumping prices to free lance photographers and authors these times. It is not different in Germany. Only about two years ago the head of the photo department of a daily newspaper in Berlin told me, that they pay for an ORDERED title page picture of a politician something less than 100 euro. That simply is ridiculous. Also the big publishing houses lowered the amount of money they would pay to a freelancer per day massively. A friend of mine quit doing this kind of job a few years ago when the price for a day doing photo journalism went down from 600 to 300 or less for a freelancer. On the first view you might say: wow 300 euros. But you do not know how many days a month you will get jobs. And you have to buy all your camera and computer equipment yourself from your income. So, I understand all your decisions very well.

Your first book was one for the South Dakota Tourism Department then? When did the idea come up to produce books from photo to design together with Camille? Actually to found a publishing business? What was it about?

Paul Horsted: The first books I contributed photos for were AFTER I left the Tourism Department and began freelancing. I worked with a publisher for a book on South Dakota (a guide book) and a book on Custer State Park. I used some images I had taken on my own while freelancing, and some I made specifically for these books.

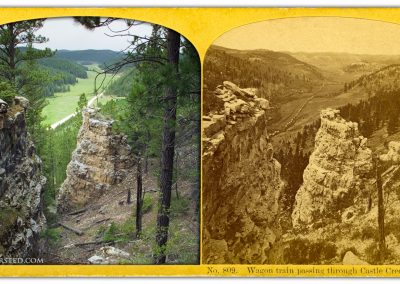

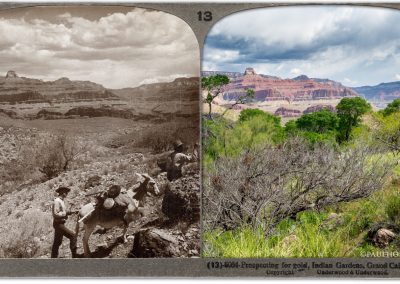

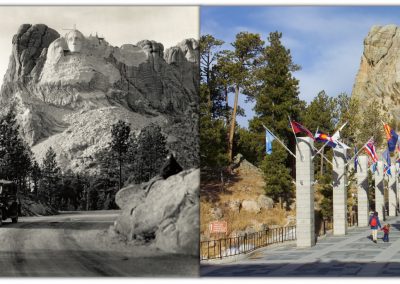

The first book we produced ourselves (in 2002) was the one called “Exploring with Custer: The 1874 Black Hills Expedition”. General George Custer (who is best known for being defeated and killed by the Sioux at the Little Big Horn Battle in 1876) had explored the Black Hills in 1874 (2 years earlier). He had a photographer with him, William Henry Illingworth, who took the very first photos of this area on glass-plate negatives. Some of these places are only one kilometer from my home. I got interested in this photographer and in looking for the places where he had set his camera. This was my introduction to “re-photography”, trying to re-create a historic photo in the modern world, to see what had changed, what had remained the same, and learn about history. I started doing this kind of work in 1999.

This 1874 Expedition discovered gold in the Black Hills, leading to the gold rush, Deadwood and its characters, and a lot of history that followed. So it is a primary event in the history of the Black Hills, and we thought it was a very important idea for a new book.

I worked with an outstanding writer who became my co-author, Ernest Grafe. Ernie was interested in mapping the trail of this Expedition, and in editing diaries and newspaper stories from those who were with Custer in 1874. This would give us a first-hand story of their exploration, in their own words. Eventually we decided to work together. Ernie did most of the text and while I took the photographs. We approached a publisher who did historical books, but they weren’t very interested in a couple guys like us who did not work for a university or have other official credentials. I had a photographer friend who had published his own book and had a good experience, and since desktop publishing was just becoming possible, and because Camille (and Ernie) had design experience, we decided to try to do it ourselves. The entire project took about 3 years. We didn’t know if we would be able to sell books or if they would remain stacked in my garage. But we believed in what we were doing, and got some good publicity while working on it. There was a lot of interest in this subject and we sold out of our first press run of 4000 books in about 8 weeks. After 15 years this book still sells very well with nearly 30,000 copies in print. We will probably update it in the next couple of years.

The success and sales of that book helped me have the confidence (and the financing) to produce the next book project, and then build on that to do the others. Camille continued to design them for us, and they are beautiful books. Sometimes “self-published” has a bad meaning, but in all honesty I believe our books look as good as any „coffee-table books“ out there. I started doing slide programs for bus tours, conventions, historical groups, schools and anyone interested in the history of our area. I’ve done hundreds of these presentations now and often am paid to do it. I enjoy sharing my work this way very much.

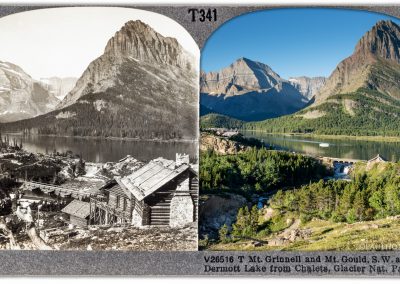

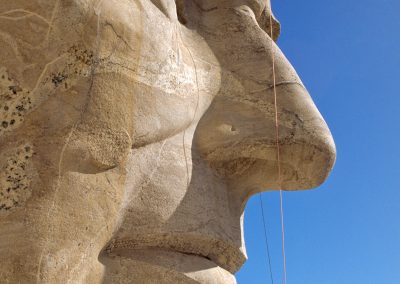

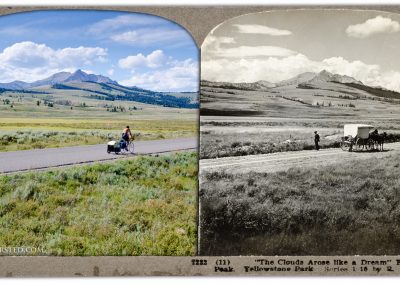

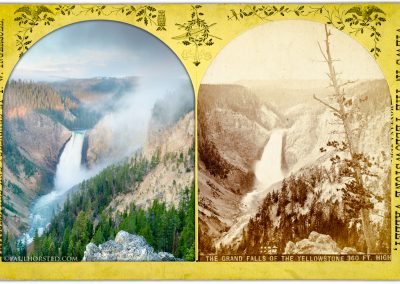

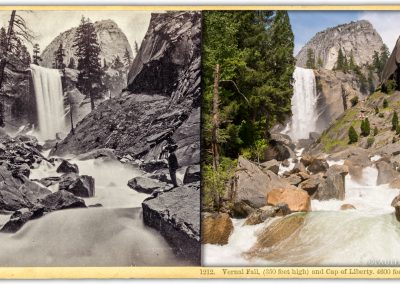

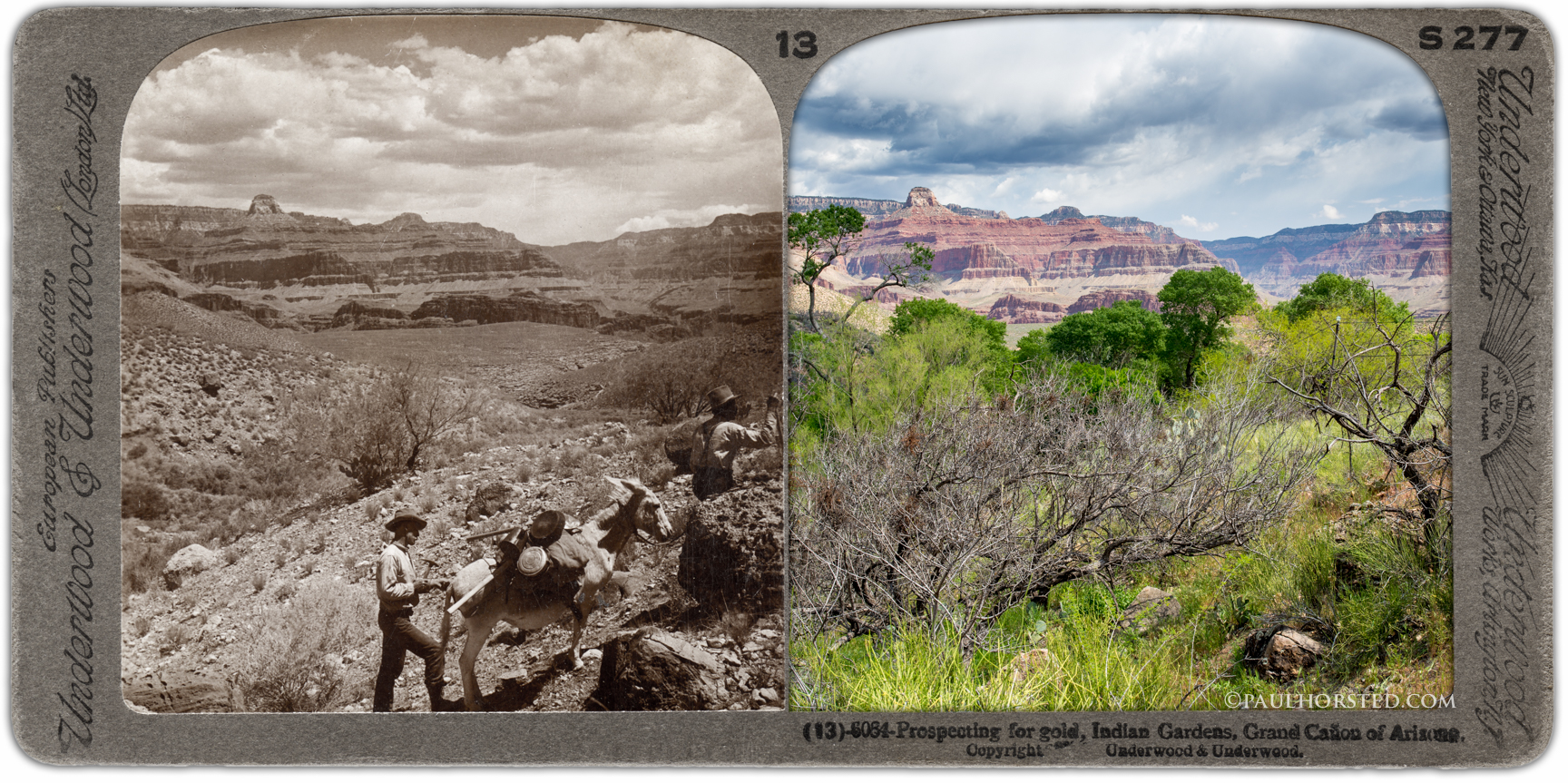

Our second book was “The Black Hills Yesterday & Today”, which again used “re-photography” of 100-year-old photos to show the gold rush and development of the Black Hills area. It is a large coffee-table book and has also sold very well for many years. We did another small book about landscapes and wildlife of our area called “Custer State Park”. Then we did another book on the 1874 Custer Expedition, which followed the rest of their trail (about 1000 kilometers) to and from the Black Hills (our first book had only covered a few hundred kilometers within the Black Hills area). Most recently, I worked for 2 years with “re-photography” in Yellowstone National Park. “Yellowstone Yesterday & Today” was published in late 2012 and is now sold in gift shops and visitor centers at this National Park about 6 hours from where we live. I am now working on “Our National Parks Yesterday & Today”, featuring 25 National Parks across the United States. This is a multi-year project, which I hope to publish in late 2017. It takes a lot of travel and a lot of time to find the exact location of these historic photos from 100 or 145 years ago. Sometimes I am hiking 15 kilometers or more to reach a place where someone took a photo in 1880. But I really like it a lot.

So re-photography has now become my passion. Every historic photo site I look for is like going on a treasure hunt, I never know what I will find. I still like doing “my own” landscape and other photography, but there is such a glut of this kind of work available now in every corner of the internet, much of it quite outstanding, that it’s difficult to do something original and make a living from it, in my experience. I do love history, and re-photography is a way I’ve found to connect to these past times and places. Publishing books has been a way to “add value” to the photographs and make them available to a wider audience than I could with print sales only.

Our books seem to take at least 3 years, and maybe now 5 years for the current National Parks book project, to complete. I try not to worry too much about the long timelines, I want to do them right as I hope they’ll be around for 10 or 20 years. Or maybe 100 years? Although I believe digital files can survive that long, I’m glad to have these images printed in a book.

Jens Pepper: How do you get the old photos? Do find them in libraries? Or do you buy them at flea markets, galleries and auctions? If so, are you also a collector of old photography?

Paul Horsted: Originally, for our first two books about the Black Hills area (“Exploring with Custer” and “The Black Hills Yesterday & Today”) I started scanning photos I found in local museums around the Black Hills. I began this process early in the “digital age” before museums had started scanning their collections, so I was able to help some of these museums by digitizing their historic photos (and also get permission to use them for our books.

Today there are quite a few sources of good-quality scans online, which are sometimes available free of charge…the U.S. Library of Congress (which is our Copyright Office also) is excellent. Other web sites may have a low-resolution or watermarked scan available online in a searchable database. These low-resolution scans are often good enough to use for my “re-photography”…if I am able to find and re-photograph the scene, I will then contact the archive and pay for a high-resolution scan (and get permissions if needed from the archive.)

But I also watch eBay and other online auctions for material, especially now for my National Parks project. It is possible to buy 130-year-old stereo view images for a few euros, though sometimes they cost more. Many popular 1800s views of National Parks were published with thousands of copies so prices are low, but then there are also uncommon images which may cost more, and are interesting enough to me to pay perhaps 100 euros.

After I’ve visited a National Park and become familiar with its landscape, when I return home and watch eBay, I may see an antique photograph that I “know” will work well for re-photography, because I’ve been near that location already. These I try to purchase.

So yes, I am a collector now, I have a few hundred historic images of the Black Hills and a growing collection of National Parks historic photos, and additional digital copies acquired from many sources.

I am looking for the simplest, least expensive path to acquiring digital copies of significant historic photos for use in re-photography. Sometimes that means finding them already scanned online, and sometimes that means simply buying them on eBay and scanning them myself. The least efficient and most expensive method is looking around in antique shops or traveling to museums or archives around the country, so I don’t do that very often. However, once in a while I’ll hear of a good collection and go visit to see what is there if they don’t have it digitized already.

Jens Pepper: If you use old photography in your books and lectures, do you have copyright problems once in a while? In Germany an artist, author or photographer has to be dead 70 years before there is free access to the created works.

Paul Horsted: It’s a good question. As a photographer myself, who has had my work “stolen” a couple of times that I’m aware of, I try to never violate another photographer’s copyright. In the United States, our Copyright Office states that any work created before 1923 is now in the public domain (no longer under copyright protection) and can be used by anyone who has acquired a copy. After 1923, the work or photo had to be re-registered after 28 years to continue the copyright, otherwise it falls into the public domain.

Because of our copyright law in the United States, I believe it is unlikely that most photographers who took a photo in (for example) 1930 re-registered their work in 1958. The Copyright Office says less than 15% of copyrights were renewed properly before 1961 (including quite a few movies, by the way.) If not renewed, the work is now in the public domain (meaning anyone can use it now.)

I use many old photographs from before 1923 (most are 1860s-1900), so these are free of copyright. I use a few postcard images which may date to the 1920s and 1930s…we can only guess the year from clues such as clothing on people or old cars in the photos. For these later images, if there is a photographer credited or other information, I try to find and contact descendants or heirs and obtain permission to use the images. It’s sometimes a difficult process to find anyone who is interested or even knew about the images. I do my best, and publish a notice in our books inviting anyone with information about photographers to contact us to let us know. I’ve never had such an inquiry.

I have studied this confusing issue, but I am not an expert on it, and my comments should not be used as legal advice about copyright law in the United States! More information is in these links below, but be aware these laws differ between the United States and other places in the world. Let me give you two interesting links: https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Copyright_renewal , and this chart, which is extremely helpful for determining copyright status, in the United States: https://commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/Commons:Hirtle_chart

What I try to do is credit the original photographer whenever his or her name is known (but sometimes there is no information about the photographer on these old photographs and stereo views). I truly admire what these early photographers did with their heavy, primitive equipment in very remote areas, and appreciate that they make my work and study of history now possible.

Jens Pepper: What cameras do you use for these projects?

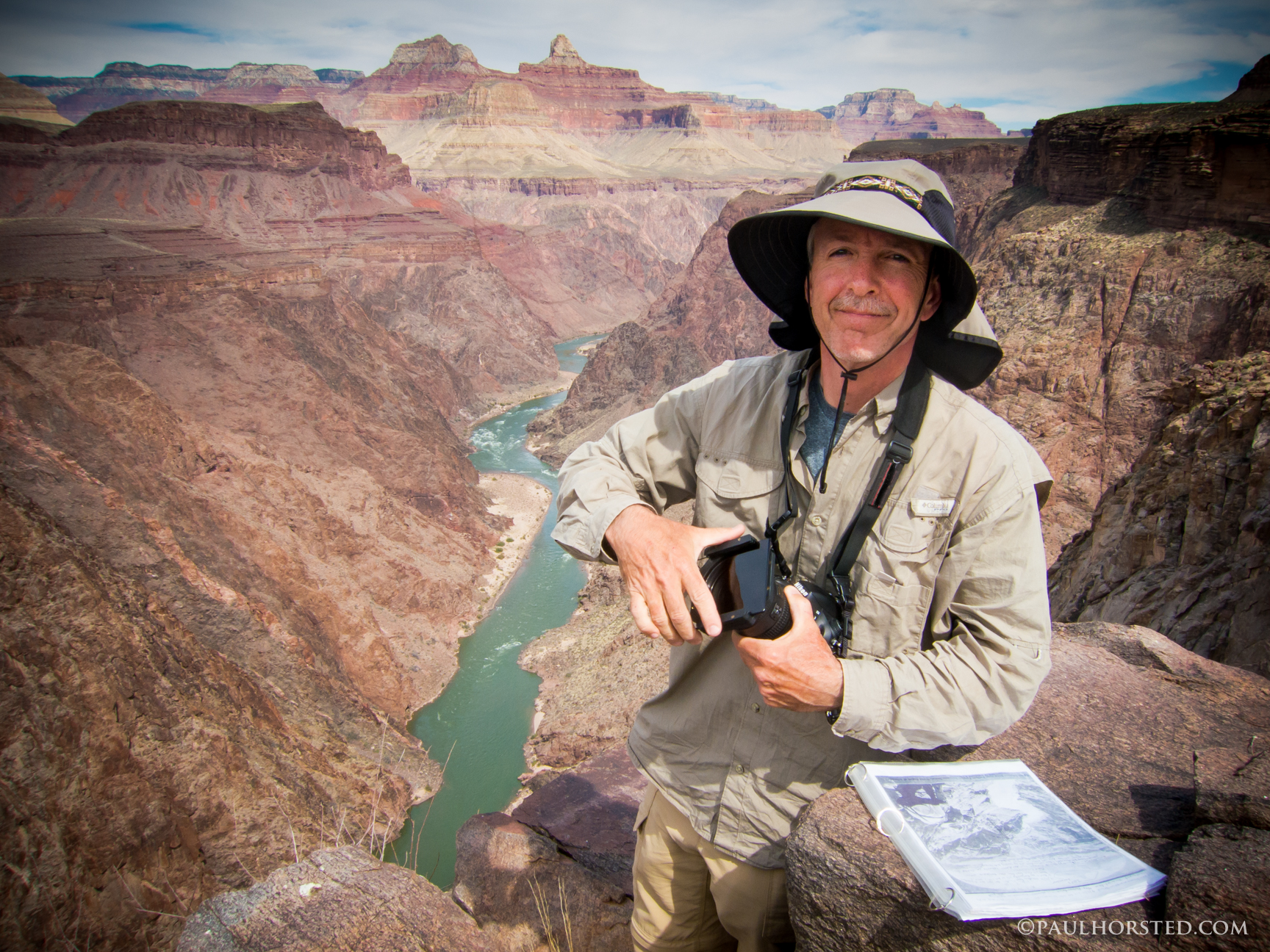

Paul Horsted: Right now I’m using two Nikon D610 cameras (one is a backup in case of failure or damage to the other). Until these cameras I would upgrade my Nikons every 2 years or so as the technology has improved. We are close to a point now where I think the only improvements may be better low-light, low-noise images (but I’m willing to be surprised by other advances!) I’m very happy with what I get from these cameras, even with greatly enlarged prints. Because I am often walking great distances, I want my gear as light as possible, and I do not need “fast” heavy lenses for the work I’m doing. I’m shooting mostly with fairly compact 18-35mm and 24-85 Nikon lenses, but will switch to a 40mm Voightländer or 50mm Nikon prime lens if they “fit” the historic image focal length and I have them along. They are slightly sharper. Many early photographs seem to be taken in the range of 24mm-50mm. I carry a quite small, lightweight carbon fiber tripod, made by MeFoto. Also an essential piece of gear is a MacBook Air, which allows me to check my work for accuracy at the location. I try to keep my backpack under 30 pounds (14 kg.) which is sometimes hard to do with the amount of water I have to carry (in desert environments), food, batteries and other gear, and sometimes overnight camping equipment as well.

Jens Pepper: Are you also doing landscape photos in all those beautiful areas you are visiting that are not for these yesterday & today projects?

Paul Horsted: As I travel or hike, I may take a few other photos of landscape and wildlife (I’ve seen a few grizzly bears, only from my car window, for example), perhaps with my phone or the small camera I carry at all times (a Sony RX100 m3 which I really like) but I’ll be honest: I don’t think I can do much that hasn’t been done in these National Parks many, many times already by thousands of other photographers. The repeat photography process however is more unusual. It takes a lot of effort and some expense to acquire the historic photos, get to the site hundreds of miles from my home by airplane, car and on foot, find the exact location, and do it well, and I’m proud of that effort and of doing something that has not “already been done” many times over.

When I’m out in these parks, I know my time is limited to the hours of daylight each day, and to the number of days I will be able to stay, and to my physical endurance. I feel the “clock is ticking” at all times, and I travel quickly to my next objective. Getting to some of these remote locations, and actually finding the site of the historic photo, and then placing the camera absolutely precisely where it was 100 years ago, all of this takes a lot of time. I try to maximize the number of re-photography shots I can do within these limitations. If I can do 2 or 3 shots in a day, I’m doing very well. Sometimes I get no shots done because of bad weather, or the light is very wrong, or I reach a site to find it is completely overgrown with trees and bushes and there is really no photo to be taken at the historic photo site (unless I want a closeup of leaves and branches!)

I try to enjoy the beauty that is all around me, and I will stop to admire a snake crossing my path or amazing waterfalls or geysers or 1000-meter cliffs below or above me! And maybe I will snap a photo or two for my personal album or to share on social media.

Jens Pepper: What will follow, when you finish your current project? Do you have a certain project in mind already? Or do you have a dream of something you would love to do?

Paul Horsted: I have at least another year of photography and work to do on the National Parks book project, and producing the book also will take additional time. But after that, I would like to do a book about South Dakota Yesterday & Today. It will be much simpler to complete, but I think will be interesting also. There are towns that no longer exist, and landmarks that have changed. In the old days often photographers would climb a water tower or a grain elevator to take a photo of these early towns (many towns here did not even exist until 1880 or 1890, unlike in your country!) Today, the water tower or grain elevators probably do not exist, so I am thinking of using a drone to re-photograph from the same height over these places today.

Otherwise I hope to keep speaking to groups and doing book signings as I have done in recent years. We have learned that it is not enough to publish a book, you must also publicize it to let people know its available, which is a lot of work and time as well. But I hope I’ll be returning to many of these National Parks for lectures or book signings in the years to come.

I’ll close by saying I feel very fortunate to be able to do this kind of work which I’ve come to love. I couldn’t do it without my wife and designer Camille, and our daughter Anna Marie, now in 8th grade. I also often remind myself I couldn’t do this without all the people who buy and read our books. I’m grateful to each reader for making it possible to follow my passion.

Das Gespräch entstand im November 2015 via Email.

Image Gallery: click to enlarge:

Paul Horsted

www.facebook.com/AuthorPaulHorsted

Paul’s current project:

paulhorsted.com/Our-National-Parks-Yesterday/

Samples of Paul’s books:

tinyurl.com/InfoPaulsBooks

Dakota Photographic LLC & Golden Valley Press

24905 Mica Ridge Road

Custer, SD 57730

605-673-3685

horsted@dakotaphoto.com

www.dakotaphoto.com