„Berlin Wonderland wird nicht das einzige Buch von bobsairport bleiben.“ – Anke Fesel und Chris Keller im Interview

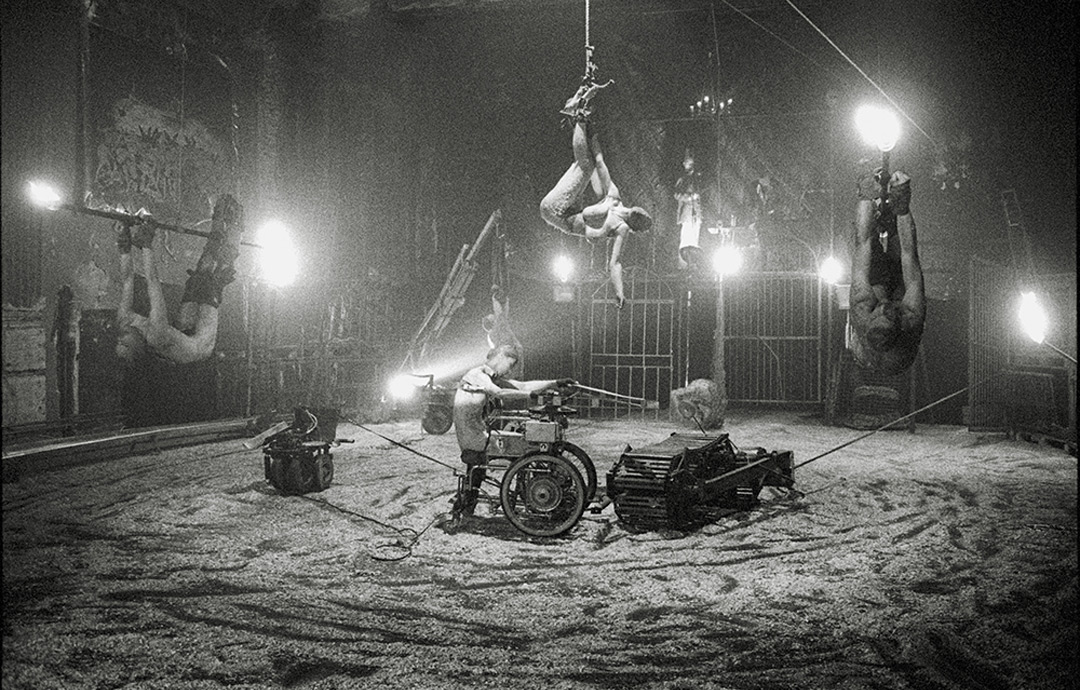

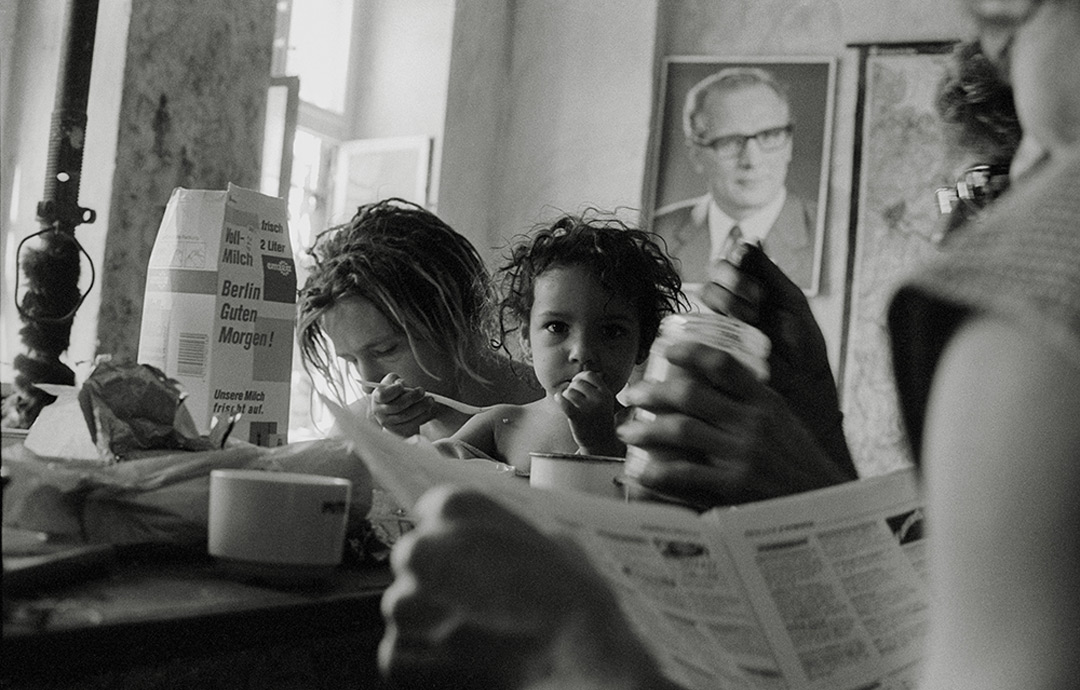

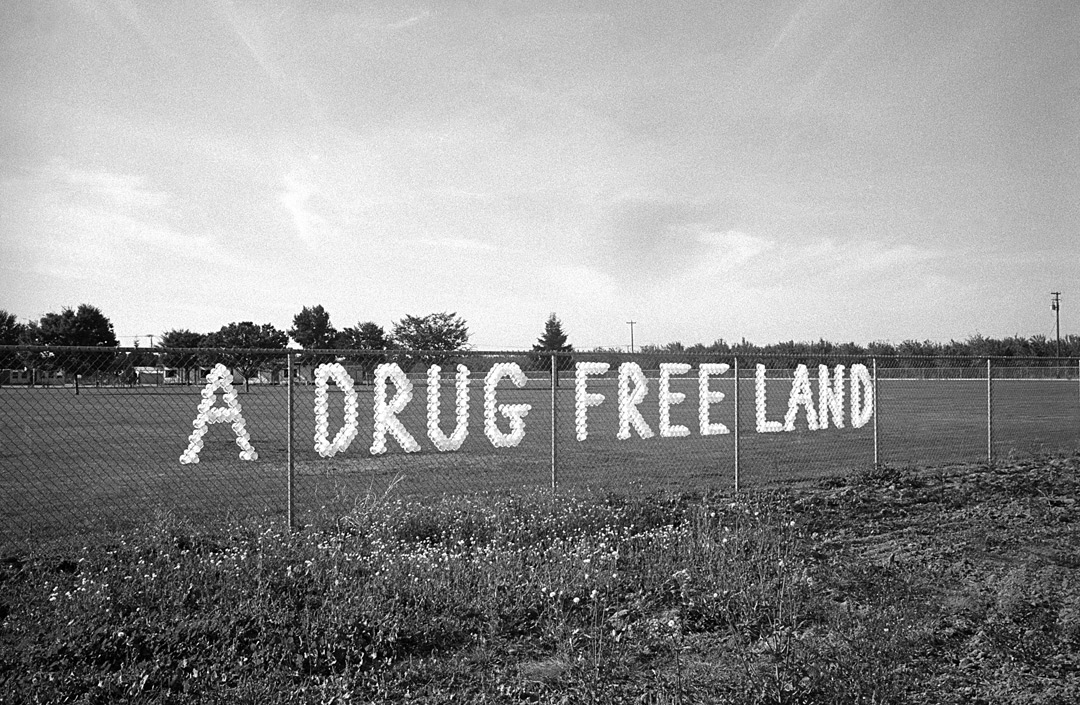

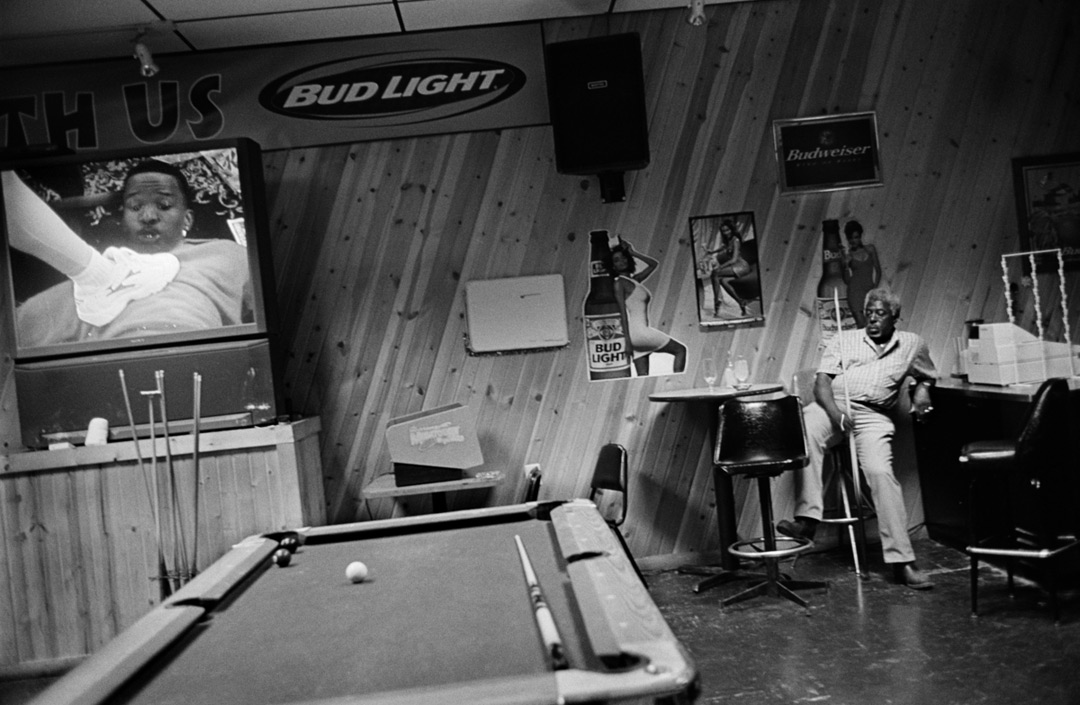

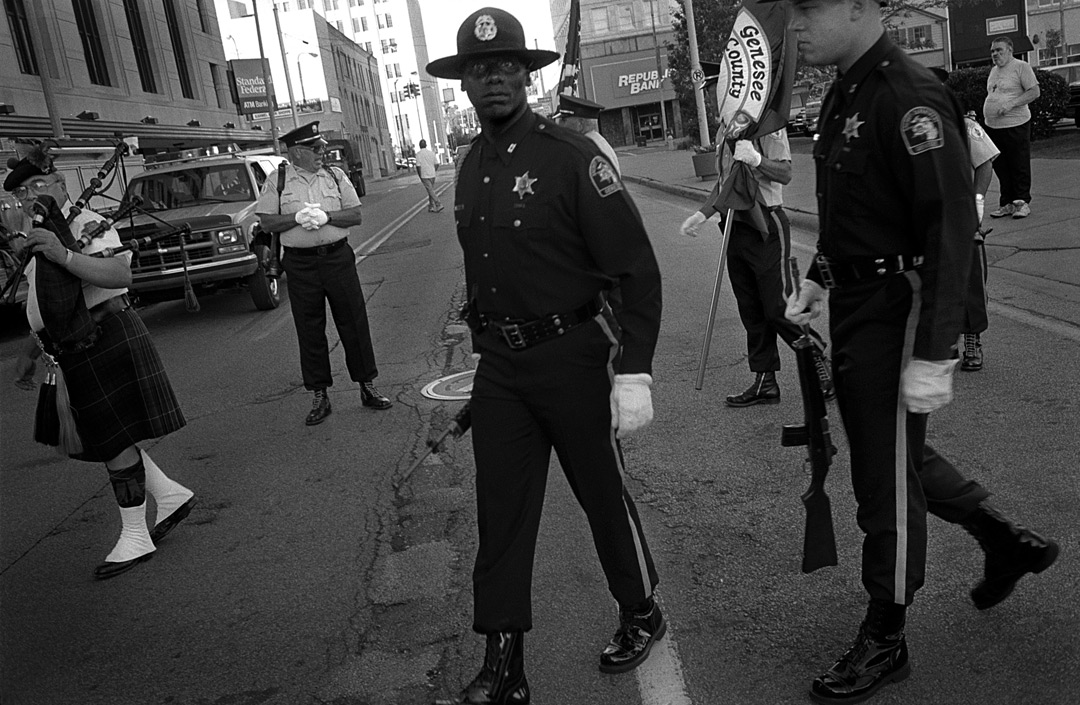

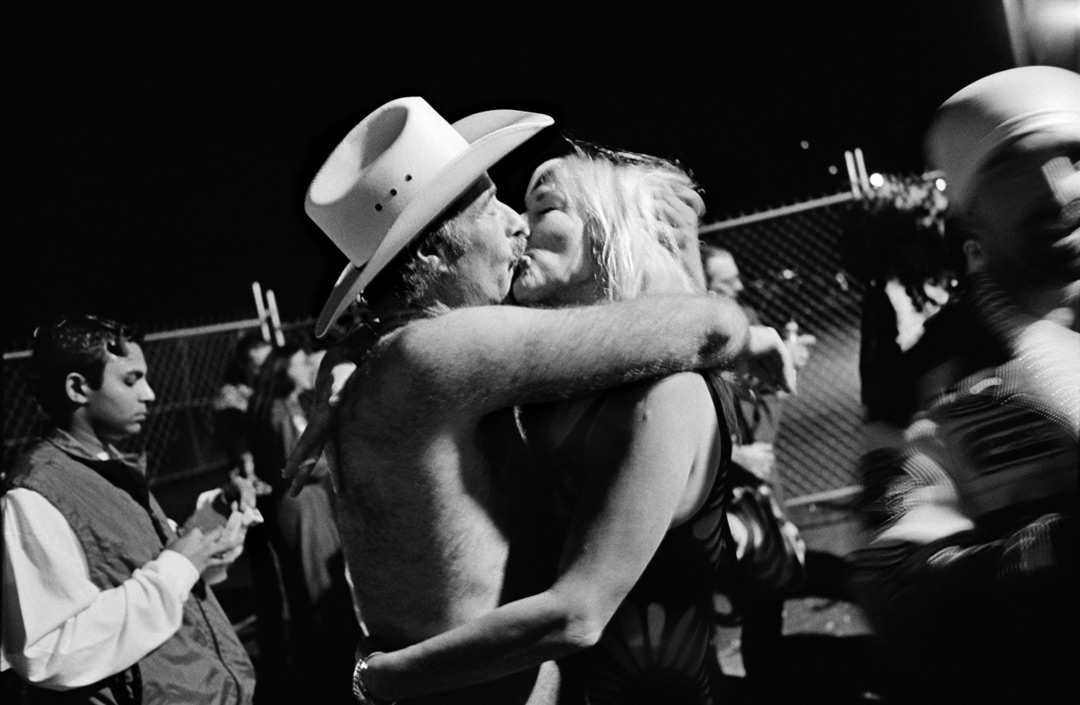

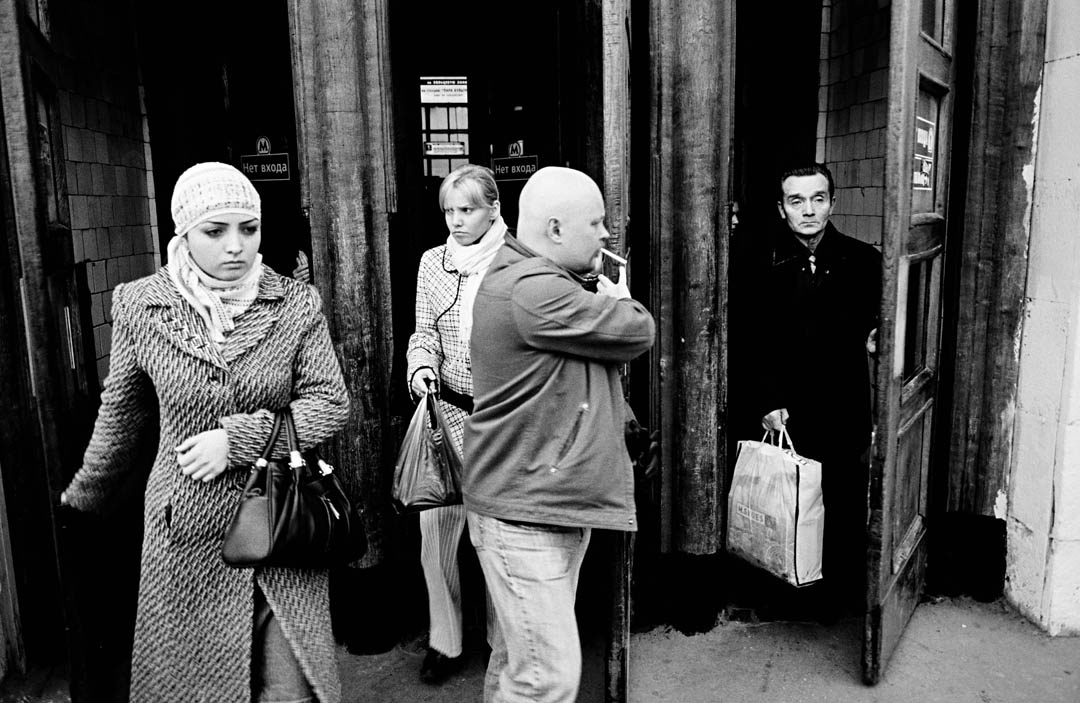

Fotos: Ben de Biel (1, 2, 4, 5) und Rolf Zöllner (3, 6) aus dem Buch „Berlin Wonderland“

Christian Reister: Wer ist Bob?

Anke Fesel: Bob ist die Kurzform für bobsairport, eine von uns – Anke Fesel und Chris Keller – 2007 in Berlin gegründete Fotoagentur. Der Name geht auf eine whisky-selige Anekdote von Tom Waits zurück, die er in der Bühnenshow zu „Big Time“ erzählt: „Well… I had a rough flight down here, you know. I don’t know, we came in… we didn’t come into L.A. actually, we came into Bob’s Airport! (laughter) Eh, actually my reaction was the same as yours. Eh, but when you think about it, Bob’s there all the time, you know? It’s very simple, they have a little lobster bar there and eh… I gotta introduce you to Bob, you’ll love Bob.“

Christian Reister: Aja, verstehe: der Name bobsairport gibt für eine Fotoagentur also ungefähr so viel Sinn wie Obst und Muse für einen Blog mit Gesprächen über Fotografie. Was hat euch vor acht Jahren dazu veranlasst den Fotomarkt um eine weitere Agentur zu bereichern? Wo lagen und wo liegen heute eure Schwerpunkte und was unterscheidet euch von anderen Stockagenturen?

Chris Keller: Anke hat mit ihrem Grafikbüro ja schon lange Buchcover gestaltet, für die wir auch viel selbst fotografiert haben. 2005/2006 wollte die Bildagentur photonica eine Auswahl unserer Fotos in ihr Portfolio aufnehmen. Leider wurden sie genau zu dem Zeitpunkt von Getty aufgekauft. Getty und Corbis verleibten sich damals viele der kleineren spezialisierten Agenturen ein und es wurde immer schwieriger, in diesen riesigen Archiven taugliches Bildmaterial zu finden, das sich für die Gestaltung von Buchcovern eignete. Aus dieser Situation entstand die Idee, dem Missstand mit einer eigenen Agentur zu begegnen. Der Schwerpunkt bei bobsairport liegt in der Buchcover-Fotografie, es zeigt sich aber, dass die Kollektion auch für Magazine und Feuilletons interessant ist. Wir möchten die einzelnen Fotografen und ihre Bildsprache zeigen und bieten die Bilder ausschließlich in Form von RM Lizenzen an.

Christian Reister: Eure Website listet über 80 Fotografen, die meisten sind zumindest unter Insidern in Berlin recht bekannt. Wie würdet ihr euer Spektrum beschreiben? Was muss ein Fotograf mitbringen, um bei euch aufgenommen zu werden?

Chris Keller: Unser Spektrum ist vielfältig, da wir Bildautoren mit einer eigenen fotografischen Handschrift vertreten. Die Fotografen müssen ein ausreichend großes Portfolio mitbringen, wobei egal ist, ob das Material sw oder farbig ist, analog oder digital aufgenommen wurde. Eine Besonderheit von bobsairport gegenüber anderen Bildarchiven besteht darin, daß wir keine Kollektionen vertreten, sondern uns ganz auf die Arbeit mit unseren Fotografen verlassen. Durch dieses Vorgehen und die damit verbundene Verfahrensweise, das Archiv aus handverlesenen Motiven zu bestücken, ist über die Jahre eine Sammlung mit zeitgenössischer Fotografie entstanden, die sich von gängigen Stockarchiven abhebt und Material zulässt, das mit seiner künstlerischen Position in diesem Kontext überrascht.

Christian Reister: bobsairport ist mittlerweile nicht nur als Agentur, sondern auch als Herausgeber bekannt. Oder kann man dazu schon Verlag sagen? Euer Buch „Berlin Wonderland“ über die frühen 90er in Berlin steht jedenfalls in jedem Buchladen und geht bereits in die zweite Auflage. Erzählt uns doch ein bisschen wie es dazu kam…

Anke Fesel: Die Idee zu dem Buch hatten wir schon lange. Zum einen spiegelt es unsere eigene Geschichte – wir sind beide 1990 nach Berlin gekommen und haben uns durch unsere Beteiligung an Projekten wie Tacheles, Eimer und Schokoladen kennengelernt. Zum anderen wußten wir um das großartige Bildmaterial, das sich in den Archiven verschiedener Fotografen befand. Von Ben de Biel, der ungefähr die Hälfte der Bilder zum Buch beigesteuert hat, stand eigentlich immer ein Satz Archivordner in meinem Grafikbüro, weil Ben und ich die Bilder für Flyer seines Clubs Maria am Ostbahnhof genutzt haben. Chris und er sind schon seit Schulzeiten befreundet und haben sich auch in Berlin bei vielen gemeinsamen Projekten begleitet. Hendrik Rauch, Philipp von Recklinghausen und Rolf Zöllner kannten wir durch die gemeinsame Arbeit bei der Stadtzeitung „scheinschlag“, für die ich als Gestalterin tätig war, Stefan Schilling aus dem Tacheles, Hilmar Schmundt aus dem Schokoladen und Andreas Trogisch war uns als begnadeter Gestalter vertraut.

Als es dann tatsächlich um die Realisierung des Buches ging, haben wir das Projekt verschiedenen Verlagen vorgestellt, mussten aber feststellen, dass sich niemand so recht an das Thema heranwagen wollte. Wir hatten uns fest vorgenommen, das Buch im Frühjahr 2014 und damit rechtzeitig vor dem Jubiläum zum 25-jährigen Mauerfall herauszubringen und haben es dann kurzerhand selbst verlegt.

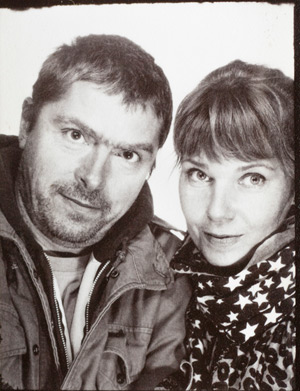

Christian Reister: Ich würde ja mal tippen, dass eure Insidersicht genau das ist, was das Buch so faszinierend macht und von konventionellen Berlinbüchern abhebt. Man merkt einfach, dass ihr dieser Szene sehr verbunden seid, nicht zuletzt, weil eure Gesichter ja auch immer mal wieder in dem Buch auftauchen. Aber auch die Buchgestaltung ist großartig – alles selbst gemacht?

Anke Fesel: Ja, für die Gestaltung zeichnet unser Grafikbüro capa verantwortlich, es war also sozusagen eine Kooperation unserer beiden Unternehmen. Dadurch, dass wir das Buch selbst verlegt haben, hatten wir auch, was die Gestaltung betrifft, freie Hand und konnten das Buch in genau die Form bringen, die wir haben wollten.

Christian Reister. Mir fiel auf, dass sehr bald nach der Veröffentlichung viele große Onlineportale (n-tv, Spiegel, Die Zeit, Morgenpost…) Bildergalerien zu dem Buch brachten, auch offline ist das Buch viel rezensiert und beachtet worden. Hat euch der Vertrieb – der „Gestalten Verlag“ – viel von der Pressearbeit abgenommen oder habt ihr diesen Part selbst übernommen?

Chris Keller: Unser Vertrieb Gestalten hat eine hervorragende Pressearbeit gemacht und zudem hatten wir natürlich auch einige eigene Kontakte. Es ist aber auch so gewesen, daß das Thema von der Presse sehr dankbar aufgegriffen wurde.

Christian Reister: Anke, du hast gesagt, ihr seid beide 1990 nach Berlin gekommen. Ihr wohnt noch immer in Berlin-Mitte, auch die Agentur hat ihren Sitz in Mitte. Das ist ja jetzt fast ein viertel Jahrhundert! Kriegt man da nicht auch mal den Mitte-Koller? Und hättet ihr die Wahl – würdet ihr euch die 90er zurückwünschen?

Anke Fesel: Wir sind immer noch gerne hier, auch wenn wir nicht jede Entwicklung begrüßen. Das funktioniert aber nur, weil wir auch versuchen, die Stadt so häufig wie möglich in verschiedene Richtungen zu verlassen. Das gelingt nicht immer gleich gut, während wir das Buch gemacht haben z.B. überhaupt nicht, dann droht doch Lagerkoller. Ich glaube, die 90er wünschen wir uns beide nicht pauschal zurück. Ich vermisse aber das Unfertige, Unperfekte und Improvisierte dieser Zeit.

Christian Reister: Plant ihr als bobsaiport weitere Bücher oder werdet ihr euch jetzt wieder mehr auf die Agentur konzentrieren?

Chris Keller: „Berlin Wonderland“ herauszugeben hat uns schon sehr viel Spaß gemacht. Es war ja auch eine sehr gute Gelegenheit, unsere unterschiedlichen Tätigkeitsfelder in einem Projekt zusammenzubringen. Dass das Buch mit so viel Interesse aufgenommen wurde, ist für uns natürlich zusätzlich ermutigend. Ich denke, es wird nicht das einzige Buch von bobsairport bleiben, auch wenn wir uns nun verstärkt wieder dem Tagesgeschäft der Agentur zuwenden werden.

Ausstellung

Noch bis 22.11.2014, Mo–Sa 12–18 Uhr

Gestalten Space, Sophie-Gips-Höfe, Sophienstraße 21, Berlin Mitte

What we found and what we lost

Fr 21.11.2014, 17 Uhr, Radialsystem V, Holzmarktstraße 33, 10243 Berlin

Ein langer Abend mit Filmen, Performances, Diskussion, Suppe, Ausstellung und Musik.

Filmbeiträge Klaus Tuschen und Marco Wilms

Diskussion mit Tim Renner, Dimitri Hegemann, Christoph Langscheid, Steffi Lotta, Christoph Klenzendorf, Jutta Weitz, Brad Hwang und Francesca Miazzo, Moderation Jochen Sandig und Chris Keller

Performance Marva Maschin Klan

Videoinstallation Manuel Zimmer – AK Kraak

DJ ED 2000

mehr Informationen unter www.radialsystem.de

Die Bildagentur bobsairport wurde 2007 von der Gestalterin Anke Fesel und dem Musiker und Fotografen Chris Keller in Berlin gegründet. Das Archiv der Agentur umfasst eine hochwertige Auswahl zeitgenössischer Fotografie.

Mit dem Bildband „Berlin Wonderland“ trat bobsairport 2014 erstmals auch als Verlag in Erscheinung.