„In the end the book is the thing that lasts“ – Christian Reister in conversation with Ken Schles

Ken Schles, Book trailer for „Night Walk“

Christian Reister: The photographs in your current exhibition at Deichtorhallen, Hamburg, were taken in New York’s East Village in the 1980s. They’ve been published in your books Invisible City (1988, re-published 2014 and reprinted 2016) and Night Walk (2014, 2016). What are the main differences in the editing of these books?

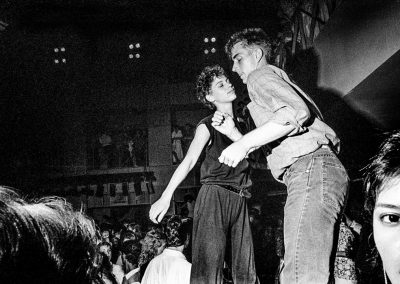

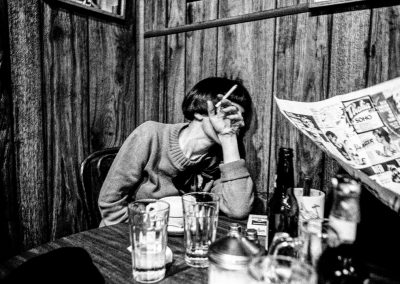

Ken Schles: I made the book Invisible City when I still lived in the East Village. I was 28 when the book came out. It was a hard time for me, a difficult place to live with the crime: …junkies …drug dealers …going to court with the landlord after he abandoned the building …having difficulties with police …all the senseless violence …the deaths from AIDS, suicides, drug overdoses. I don’t talk about any of this in the book(s) specifically, but I think there’s a mood, a sensibility that comes across.

Night Walk had a different genesis. I made that book as a look back at that time and place and those people. In Invisible City I was conscious not to repeat images of people, not to have the same person recognizable in more than one photograph. I didn’t want the book to feel like it was telling the story of any one person. But Night Walk —I wanted the images of certain individuals to repeat, to have stories interweave. I liked that in Night Walk you saw some of the same characters over and over again.

The two books also have different structures. The structure of Invisible City is not linear. The pictures are taken in different places, at different times, day to night, night to day, back and forth. There really isn’t an implied line of time running though the book. It’s almost as if everything is happening all at once, all at the same time. But Night Walk is structured as an extended, almost excessively long evening. I remember at that time for me in New York the evenings would go on seemingly forever… I’d go out and maybe see a performance or go to a gallery opening. Then there’d be dinner or a party afterwards. Then a walk through the streets – I’d go from one place to another, into a club or then to a bar, and on to the next place… by the end of the night you might end up in a quiet place, alone or in someone’s apartment. The cover image on the book shows a person walking away with the title Night Walk above him – it’s as if the’s walking into the book and it’s the beginning of his journey – but I end the book with this same image, which shifts its meaning. Now you feel like the night is over and you’re walking away into the morning light, into some unknown future. So, in editing and sequencing, Night Walk is very different from Invisible City. It’s built upon a very different kind of narrative structure.

Christian Reister: In the exhibition at the Deichtorhallen images that form the books Invisible City and Night Walk are mixed together. We don’t see just one book and then the other. It creates a third story…

Ken Schles: Yes, I think the exhibition has become a third story. It’s neither Invisible City nor Night Walk. I wanted to mix it up.

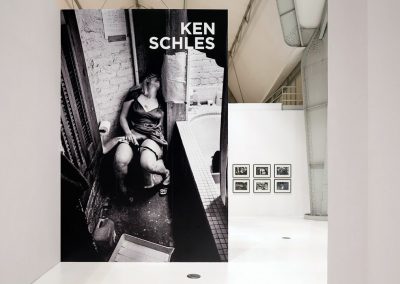

In a gallery space or in a museum you don’t necessarily go straight from one picture to the other like you might in a book. I wanted to play some pictures against others in new or unexpected ways. It’s another way to tell my story. An exhibition is very experiential. It’s about how you move through space and connect one image to the next or a group of images on one wall to another and what you might see when you turn a corner. The space here is configured like a spiral. I wanted to take advantage of that. The first big picture (of a woman passed out on a toilet) announces the exhibition and sets the tone. We painted the first wall behind it black with a small bit of text to give an introduction and further set the mood. Then there’s the main wall in a big open space that’s clad in metal. It becomes sculptural, monumental. There’s another black wall at the end. This acts like a coda, but refers to that first black wall in scale and it has a short poem by Kathy Acker applied to it in large type. Just before that wall we have the biggest image that was ever printed and mounted for exhibition in the Deichtorhallen, which you see only if you turn the corner. It comes as a surprise and takes up an entire wall. Because the Deichtorhallen is so soaring an exhibition space you can experiment with it in dramatic ways.

Christian Reister: The wall covered with aluminum plates with color stains on them: I see you’ve mounted the pictures rather classically with mats in black wooden frames on the metal. What’s the idea behind it?

Ken Schles: It was a way for me to formally change the museum space and bring another sensibility to the exhibition. There are several references here: The metal plates are used printing plates. I love books so there’s the reference to my books and to the printing process. But the initial question was how can we map this museum space and connect it to my New York of the 80s? I was thinking about Andy Warhol’s Factory – he had aluminum foil and silver paint covering the walls of his studio. Also, in New York during the 80s, the „industrial look“ was big. Many spaces were repurposed factories or slaughterhouses and some bars and club spaces would have metal walls. At the time it was installed as commentary or was simply an easy and cheap method to cover up crumbling walls. There’s also another reference for me (that I just remembered). When I moved into my place on Avenue B, I put a steel plate and deadbolt lock on the door of a room I eventually made into my darkroom. It effectively made the room into a safe. I kept all my valuables in it. Even when my apartment was broken into whatever was inside that room was kept safe. The window in that room had already been boarded over with plywood and reinforced with steel pipes. Nobody could get in there.

Christian Reister: At the official artist talk at Deichtorhallen you showed book trailer videos. Again, another way of dealing with the same images. Now combined with music and text. This adds even more layers to the work.

Ken Schles: I think all these approaches offer different entry points to the work. Different ways for someone to make contact, to make a connection. The books are a good place for the work to end. But you can enter the work from any number of points: maybe you’ve seen a video online, maybe one picture piqued your interest, or maybe you’ve read a text about it or heard a story of what New York was like at that time. You might become interested, maybe Google my name, and more images pop up. Maybe you’ll go the exhibition to see the pictures on the wall or become curious about the wall itself… or pick up a book.

They’re all different points of entry. Different ways to get to that place, to evoke that time. It allows me raise issues about being in that particular time and place, and pose the question of what it was to be and struggle and live in such a harsh place; to love and feel loss and to discover the world. They’re multiple ways to engage the viewer, points of seduction, if you will. Different ways in which the work might penetrate someone.

Ken Schles, Book trailer for „Invisible City“

Christian Reister: Have you lived in New York your whole life?

Ken Schles: I was born in Brooklyn [in NYC], we moved to Queens [also in NYC] when I was 5 years old, then we moved to the suburbs when I was 12. As soon as I got out of high school I ran straight back to the city with a couple of friends. I moved to the East Village when I was still just 17. All within a 50 mile radius, but mostly within a 20 mile radius.

I was very young when I moved to the East Village, so in a lot of ways I feel like I grew up in the Village. I started taking pictures for Invisible City in 1983. By then I had lived in the neighborhood for 5 years.

The City was a mess at the time. It was very dangerous, the neighborhood I was living in was one of the worst in the city. I wanted to photograph full-time but couldn’t find enough work. So I worked as a photographic printer to stay connected to it, but also had many other jobs. Jobs like the ones one has when one first is getting started. I worked as a bus boy in a restaurant, as a photographer’s assistant. For a while I drove a truck and moved art work. It was great to see how other artists worked, I met everyone from Richard Serra to Robert Longo and many, many, many other artists. I was very connected to the art scene in the East Village and documented other artist’s work for the galleries or the artists. I photographed one of Jeff Koons’ early solo shows at International with Monument on 7th Street and documented work for my friends Group Material, started by a fellow classmate of mine, Doug Ashford. Julie Ault was also a founding member. She was in a relationship with Andres Serrano, so we met before his career blew up.

Christian Reister: For a photographer I can’t imagine a better place to be than New York at the time. The „New York School“, Robert Frank, Diane Arbus, Winogrand, Meyerowitz, the ICP, Magnum etc. Did you feel connected to the „scene“?

Ken Schles: I did feel connected to the scene and this history of photography.

Christian Reister: To the history only or to the „community“ also?

Ken Schles: Both. I was working with Gilles Peress quite intimately (in a very literal sense, as the dark room in his loft on the Bowery was next to his bed). His loft apartment was in the same small building as Lenny Kaye’s place. Lenny is perhaps best known as Patti Smith’s guitarist. They lived a block down the street from CBGBs (which was around the corner from Robert Frank’s apartment – though we didn’t meet until several years later). …I felt a great connection to Gilles. I started working for him while I was still in school and continued after I graduated. It felt more like a peer relationship, not a professor/student relationship like I had with Lisette Model, for instance.

Gilles Peress was a good transition for me to see how to make one’s work in the world. He also hooked me up to some of the other Magnum photographers, so I worked as their printers too: Burt Glinn, Elliot Erwitt, Erich Lessing. And of course, in New York photography was always there – in the book stores, at the galleries and in the museums.

There was a lot of photography happening for sure, and several scenes were going on simultaneously but none of it really fit what I was doing. I was a bit of an outsider everywhere. At the time the art photography scene was heavily influenced but what was called „set up photography“ where people would use tableaux and there was also a big push to appropriate or subvert images or use them in conceptual or political practice. I’m thinking of Louise Lawler, Laurie Simmons, Sherrie Levine, Cindy Sherman, Lorna Simpson, artists like that. There were artists that were doing portraiture: Robert Mapplethorpe or Peter Hujar, Avedon. And then there were traditional documentary and editorial photographers, I think of the many artists showing with Aperture at the time, like Danny Lyon or Chris Steele-Perkins or the Magnum roster of photographers. Or photographers who might be documenting the scene and photographing in the clubs – Wolfgang Wesener, and Volker Heinze comes to mind, for example, he came here to the opening at Deichtorhallen. He did a couple of books on the a big nightclub at the time in NYC that had a connection to the art scene. A place called Area. But I wasn’t interested in using my images to promote particular venues, celebrities or any of the „scene.“ I was very careful about how my work was shown and in what context. Even in this here at the Deichtorhallen exhibit I don’t caption the images. It’s seems to me in this instance that they’re not necessary to understand the work, but at the time, what information captions contained became the primarily reason people showed interest in the work.

I was known in the community and showed my work in local galleries in the neighborhood. But it wasn’t necessarily with other photographers. At the time neb-expressionist work was big, not photography. It was the work of painters and sculptors. And then also performance artists. Graffiti artists, musicians.

The music scene was getting huge. It was the first to cross over into mainstream culture. Punk rock. No Wave. New Wave. Hip Hop was just beginning. You’d see breakdancers on the street, heard early rap music on the streets and in the clubs. „The Message“ by Grand Master Flash was the first rap song. Run-DMC, The Beastie Boys. A friend of mine had a painting studio with the graffiti artist Fab 5 Freddy. There wasn’t this separation of the different genres yet. Everybody downtown was mixing together. Gay culture, punks, artists. It wasn’t until later that these groups started isolating themselves within their own communities.

Christian Reister: Talking about the music scene – I have read somewhere that there are more than a hundred album covers with your photos in them. Alicia Keys, Lou Reed, Green Day, Spin Doctors, Dream Theatre and lots more. Did they use photos form your existing work or did you do assignments for them?

Ken Schles: Yes, but that came a little later. I was commissioned by the bands and record labels. For Lou Reed they wanted to see some personal things, pictures I shot in the neighborhood. Naked City, the avant-garde jazz group headed by John Zorn, Fred Frith and Bill Frisell, were probably the first group to get in touch with me… but most of that work came after Invisible City was out. Some creative directors at the big record labels became aware of what I was doing. One day this agent from Los Angeles called me and said „Your work is so hard …but I absolutely love it. The next time when I’m in New York we should get together and talk.“ Afterwards the music work came.

That started around 1990. I was dead broke at the time, there was a recession hitting. The art market bubble burst and the East Village gallery scene was collapsing so I jumped into the music world. It was a ton of fun because I worked with creative directors who said „we love your work, we think it’s a great match for this band or such and such an artist.“ Sometimes I would hang out with the artists and we’d develop ideas together. There was lots of travel – New York, Seattle, Los Angeles, wherever. Those may have been assignments, but they were very creative, not to mention fun to produce.

Christian Reister: So you finally made your living as a commercial photographer?

Through the years I’ve done a lot of commercial work. I’ve always loved the collaborative aspect of it. And it wasn’t just straight commercial work that I was doing. I was shooting a lot of documentary and portraiture. I’ve had six covers of Newsweek, I’ve done feature stories for the New York Times Magazine or FAZ and Tempo here in Germany. It was a big range of work. I was always excited to find myself in new situations. I think it’s broadened my world view and given me insight to people and places I would’ve never had access to.

Now I try to focus mostly on my own work – to write, to do books and exhibitions. It’s a good thing for me to focus on right now. I see now how so much of the commercial and editorial work was utterly disposable.

Christian Reister: As you know, I live in Berlin and we have this very successful photography exhibition venue called c|o Berlin. You did a solo show there when they were still located at Linienstraße, Mitte, before they moved to the much bigger Postfuhramt, Oranienburger Straße, right?

Ken Schles: Yes, it was the first time I was in Berlin. Markus Schaden hooked me up with Markus Hartmann at Hatje Cantz for my book The Geometry of Innocence, published in 2001. The exhibition at c|o Berlin was around 2002. I met Stefan (Erfurt, head of c|o Berlin) about a year before that. He told me he was in New York for a short period of time in the 1980s. He had a real affection for my work and what it depicted. At first we were talking about showing Invisible City but by the time we met, I was already working on The Geometry of Innocence for 12 years. So when that book was published it seemed to make the most sense.

Christian Reister: How is it working with Steidl?

Ken Schles: Oh! I’ve had the whole Steidl experience. In more than one way too… (laughs). We were supposed to have reprints of my books ready for the opening here at Deichtorhallen but… but… I mean, even saying that, I really respect what he does and how he does it! For Gerhard there are always openings here and there and so, because of that, there’s often deadlines everywhere. Yes we should try to meet those deadlines, of course, but in the end the book is the thing that lasts. Forever. And I have always felt that as well.

In the end it’s the book that matters and things that really matter shouldn’t be rushed. One needs to be precise about it. To go to Göttingen and stay at Steidlville was like going on a spiritual retreat, except it’s a retreat for photobooks. Gerhard (Steidl) has done tens of hundreds of books at this point and he has more than a thousand in his library. If it takes a couple of more weeks to make a book right – take a couple of more weeks. Don’t compromise the book. Because once it’s done, you can’t go back and fix it. There’s no fixing it.

I think that’s something that’s missing in much of the contemporary photobook world. There’s a sense of – well, you can produce books pretty easily now, the technology is easily accessible. You can show things in process too. I understand that desire and understand that the technology and all the various platforms allows us – even encourages us – to take that kind of approach. But I don’t know if it’s always the right solution. The technology, the platforms, social media – they open us up to new avenues for thinking and allow us to explore ideas in new ways, but we have to decide whether we want to go down those avenues. We have to decide and ask ourselves – especially if we have a statement to make: “Should this be the final form? Is this really the best way to say what I have to say?” We have to take care.

Christian Reister: Thank you very much, Ken, for taking your time.

Ken Schles (* 1960) is a photographer based in Brooklyn, New York.

Photobooks: Invisible City (1988, 2014, 2016), The Geometry of Innocence (2001), A New History of Photography: The Word outside and the Picture in our Hands (2008), Oculus (2011), Night Walk (2014, 2016).

Portrait by Christian Reister